Introducing A Danger Shared

The following text and images were excerpted from the introductory chapter to the book A Danger Shared: A Journalist’s Glimpses of a Continent at War (Blacksmith Books, 2024), which features photography by wartime foreign correspondent Melville Jacoby and accompanying text by Bill Lascher, who wrote about Jacoby in the critically acclaimed 2016 book Eve of a Hundred Midnights: The Star-Crossed Love Story of Two WWII Correspondents and Their Epic Escape Across the Pacific (William Morrow & Co.).

The 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War had just passed when I began writing this introduction on September 11, 2020. That date also marked 104 years to the day since the birth of Melville Jacoby, the American foreign correspondent whose images of the war comprise the majority of those included in this book. Mel’s life was short but impactful, capped by a career a close friend called “as brilliant as it was brief.” That brilliance Mel devoted to covering the war and bridging the distance between two physically and culturally distant lands: the United States and Asia.

Mel documented the war and its impact as part of a broader mission to help Americans better understand China (and, later, the Philippines and the place then known as French Indochina). Having studied, lived and worked in China, Mel was understandably interested in how coverage of the war might influence Americans’ sympathy, or lack thereof, for his Chinese friends, neighbors, and colleagues. He also foresaw the weighty implications of the conflict for the United States. Interdependencies and connections had been evolving between Pacific-facing nations before the war. Mel understood this impact on the Pacific and how the conflict between the people and societies on one side of it increasingly mattered to those on its opposite shores.

That morning in 2020 I was, of course, writing amid another crisis: the Covid-19 pandemic. The coronavirus outbreak and responses to it were widening pre-existing political, social, and cultural rifts. This reminded me of a similar crisis, the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920, which claimed Mel’s father’s life when Mel was just two years old. I put this collection together because our lives are more connected than we often realize or care to admit. Wherever and whenever we live, we deserve to have our stories remembered. Our memories are intrinsically valuable, but we are also better able to highlight our connections when we take effort to surface and preserve not just our own stories, but those around us.

The anniversary of the Second World War’s end passed quietly. Our year of contagion, political unrest, and climate catastrophe obscured any inspiring observances of the victory over fascism, moving appearances by veterans, or somber reflections upon atrocity and sacrifice that might have been. What could have been a year of remembrance instead was drowned out by the noise of “2020,” a term that became popular shorthand for calamity and left little room for memory.

Tens of millions of people were killed and displaced during the war in Asia, where the conflict’s global consequences still resonate. Still, Asia’s experience of the war remains largely an afterthought in other parts of the world. Even before the pandemic, the war in Asia was not widely remembered elsewhere. For three quarters of a century, countless tomes about World War II have dissected every nuance of the struggle for Europe, and most of those that don’t instead address America’s crusade through the Pacific. In the Americas and Europe at least, comparatively few titles document the conflict’s massive human and economic toll in Asia, where fighting began two years before Germany invaded Poland and four years before that infamous Sunday morning in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Melville Jacoby at the Press Hostel

Melville Jacoby sits in front of the ruins of the Press Hostel in Chungking in the summer of 1941. In the photo, Mel clasps a flashlight, suggesting he’d just returned from one of the city’s dark, dingy air raid shelters or was prepared to enter one at short notice.

Melville J. Jacoby Press Hostel calling card (fron

The Chinese-language side of Jacoby’s card

Press Hostel calling card (reverse)

Melville Jacoby’s calling card while working in Chungking (Chongqing), China, circa 1940-1941

This collection can’t fix that reality, but it may help resurface the story of Asia’s experience of the war while reviving the memory of those who tried to chronicle it. Many of the images you see within this collection have never been published. Curating and interpreting them has expanded my knowledge of World War II, shifted my understanding of war in general, and deepened my appreciation for those who sacrifice their lives to document world-rending moments.

The Faces I see every day

A photograph of mostly Chinese nationals photographed by Melville Jacoby, who wrote “The Faces I See Every Day” on the back of the print. Mel likely made this image while a student at Lingnan University in Canton (Guangzhou), China, in the 1936-1937 school year.

That deepening began twenty years ago, when my grandmother — Mel’s cousin — gave me a typewriter that used to belong to him. I was in my early twenties. As I learned more over the ensuing years, that story has maintained a presence in my mental landscape. Learning about Mel was at first an excuse for me to spend time with my grandmother. She’d ended up with most of his possessions, and each time I visited, I learned a bit more about him. By 2016 I’d gathered enough material to write my first book, Eve of a Hundred Midnights (William Morrow), which describes Mel’s life, his romance with the equally remarkable journalist Annalee Whitmore Jacoby, and their escape together from the doomed Philippines.

As interesting as those two were, there was a bigger story to tell. That book really only touched upon a small segment of what’s contained in the hundreds, maybe thousands of photographs, letters, and notebooks of Mel’s I’d grown to look forward to seeing at my grandmother’s house (let alone elsewhere). Mel and Annalee’s story was worthy of a book, but leaving out all this other material did a disservice to the work they and the people close to them produced. These young, passionate reporters had written exhausting, illuminating accounts of the war — both for private and public audiences. They also captured vivid images of conflict as well as the beguiling way everyday life persists in spite of it. What good were these chronicles they’d devoted their lives to capturing if they remained stuffed in some closet in California for decades?

I regularly reflect on what didn’t make it into my book’s pages. I’ve focused on telling other stories since, but part of me still thinks about the ones Mel told, the ones he didn’t tell, and the ones nobody had a chance to tell. More than any of that, I wonder about what stories I don’t even know about, which stories were left untold and forgotten by the world.

This volume offers a chance to revisit some of these stories. Though Melville Jacoby worked primarily as a writer, he rarely went anywhere without a camera. The images he made over the course of his time in Asia reflect increasing comfort behind the lens. After closely examining thousands of his prints and negatives and other related collections, I’ve selected an assortment of pictures that I believe convey a sense of the world he and millions of people whose lives he chronicled experienced.

The images Mel captured reflect increasingly intimate portraits of China and its neighbors, even in their most dire moments. Candid depictions of everyday life seem ever more natural over time, though occasionally Mel’s lens reflects faces frozen in discomfort under his gaze. In some images, Chungkingers pause amid piles of rubble and chaos-filled streets — sometimes seemingly while racing to or from a barrage of bombs — to gawk at the westerner stopping to take their pictures amid the peril. It’s never quite clear whether they’re bothered, or even offended, by his presence, if other concerns have furrowed their brows, or if expressions that appear frozen for eternity as troubled looks were in fact transitory moments that passed as quickly as the shutter’s snap.

This is an imperfect and unbalanced collection. Like any storyteller’s, visual or otherwise, Mel’s career — and his eye — evolved. Hence: “A Journalist’s Glimpses of a Continent at War.” Would that Mel had taken as many pictures of Japan when he visited it at the outset of the war as he would in Chungking three years later. I wish I didn’t have to wonder which subjects Mel simply overlooked and which he elided out of fear of losing tenuous employment. It will remain a mystery what images from Southeast Asia might have survived had Mel’s dogged work not made him wary after death threats and an arrest outside Haiphong on espionage charges. And, of course, we’ll never know what was lost on New Year’s Eve, 1941, when Japanese forces approached Manila, leaving Mel and his Time Inc. colleague Carl Mydans with no option but to incinerate their reporting material in a hotel basement. For that matter, even though Mel provided the first pictures most Americans saw of their countrymen’s desperate fighting on the Philippines’ Bataan peninsula and of those soldiers’ stubborn resistance on Corregidor, I wish I could see what images of these and other embattled places he lost during his final perilous escape from the Philippines when he was forced to ditch everything but what he could carry.

War Map of China

Residents of Chungking study a large public map of China with information about aerial battles, bombing raids, and other updates about the war with Japan

Soldiers marching

A column of Chinese soldiers parade through a city street somewhere in China, likely Chungking, circa 1940-1941

Woman cooking in Chungking

A woman prepares blocks of tofu while other food cooks at a stall in Chungking

While I am originally a writer and reporter, the time I’ve spent examining Mel’s life and work sparked a personal interest in photography, archival work and preservation. I mention this to emphasize that while I’ve done my best to faithfully capture the originality of the images presented here, I have little prior professional experience in these fields. I have digitally removed dust and scratch marks introduced while scanning images, slightly adjusted tone where necessary for some images, and, with a handful, made minor crops that don’t change what I believe were the pictures’ intended composition or content. I’ve clearly labeled the few instances where I’ve made any significant adjustments. I took great care to remain faithful to each original and I think I was successful in doing so, but I also think it’s essential that I note that these are not totally untouched images.

What you see here is an incomplete record, as is any history or other collection of images and text. My understanding of Mel and the world he witnessed comes from examining his work, his correspondence, and what personal ephemera survived decades of travel, war, relocation, death and everyday life. I managed to glean invaluable perspective through conversations with a few people who met Mel and survived long enough for me to meet them. I augmented my knowledge of the context in which he worked (and the context that situates this collection) with primary sources from dozens of archival collections from journalists, academics, soldiers, sailors, politicians, and business people who grew up, lived, worked, loved or fought throughout Asia. That context was then deepened by readings from and discussions with countless other authors, historians, scholars and storytellers.

Soldiers with Stretchers

Chinese soldiers gather with stretchers on a rubble-strewn Chungking street after an air raid circa 1940-1941

Sisters on steps

China’s powerful “Soong Sisters,” Soong Mayling, Soong Ai-ling, and Soong Chingling during a tour of Chungking in April, 1940. The tour was part of a heavily publicized reunion of the sisters aimed at boosting Chinese morale during the war and cultivating sympathy from potential allies, including the United States

I cannot with complete certainty claim what any one image in this collection depicts, nor can I answer the countless questions each provokes. What was Mel trying to capture with a given photo? What moment had he hoped to record when he clicked the shutter button? Who were the people in front of his lens? Where were the places they occupied? Why were people in some images sifting through rubble or running from flames in others? Why were faces in some pictures full of tears and others brightened by smiles? What might have been left out of a frame? Where can such omissions be traced to Mel’s own actions as a photographer, and which can be explained by the haste and danger of war? What about entire images that might have been omitted? Which were left out because of Mel’s own decisions and which omissions can I attribute to the simple havoc wrought upon memory and history by the passing of years?

Multiple lenses filter my understanding of World War II in general and the war in Asia specifically. These filters include Mel’s own decision-making about what images and events to record as well as the time that passed between these decisions and my first learning of Mel’s story decades later. I mention these layers of filtration neither to excuse mistakes nor evade scrutiny, but to acknowledge that I don’t intend this collection as a definitive record of either the war or Mel’s career. Instead, I hope this project serves to prompt discussion and examination.

Hanoi canal

Residents of Hanoi, Tonkin, French Indochina (present-day Vietnam) walk along a dirt road next to a canal in the fall of 1940

I’ve been able to confirm what some of these images depict by triangulating Mel’s work with other sources, but some were more difficult to assess. Where I can confidently identify someone, or some place, or some moment, I have done so. Where I have a strong hunch of how to label an image, yet lack certainty, I have so indicated. Other images will be left to interpretation, but I included them because they remain intrinsically powerful. Perhaps you’ll wonder, for example, why sorrow seems to shadow some faces, while others betray a joy that seems impossible among all the destruction and horror. Maybe the way moments of serenity seem to persist even as tumult surrounds people will remind you of similar dichotomies in your own life. Perhaps there will be emotions on some of these faces with which you can identify, as I have many times.

Japanese tank in Hanoi

Onlookers watch a Japanese tank drive through Hanoi in the fall of 1940. After briefly resisting Japan’s efforts to move troops into French Indochina (present-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), French colonial forces controlled by the Vichy regime acceded to Japanese pressure. Following its signing of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, Japan moved thousands of troops into Indochina to cut off China’s access to munitions and other supplies

Flower seller in Hanoi

A vendor at a flower stall in Hanoi looks at a bouquet of light-colored flowers. Fall, 1940

Guerrilla with rifle

A man in local attire poses with a rifle on a bridge somewhere in French Indochina, likely near the Mekong River along the border of Laos and Thailand in December, 1940

French soldiers marching with rifles

French soldiers march with service rifles slung over their shoulders after a skirmish with Japanese troops near the town of Langson at the border of French Indochina and China in September 1940

Ultimately, I hope this collection reignites interest in a period and region worthy of deeper, sustained, and expansive discussion. We live in an an era when, I believe, we all would benefit from reflecting on history. Perhaps this collection will also prompt readers to think about stories in their own worlds that remain untold or under-appreciated, and to reflect upon how our past provides perspective on our present and informs our future.

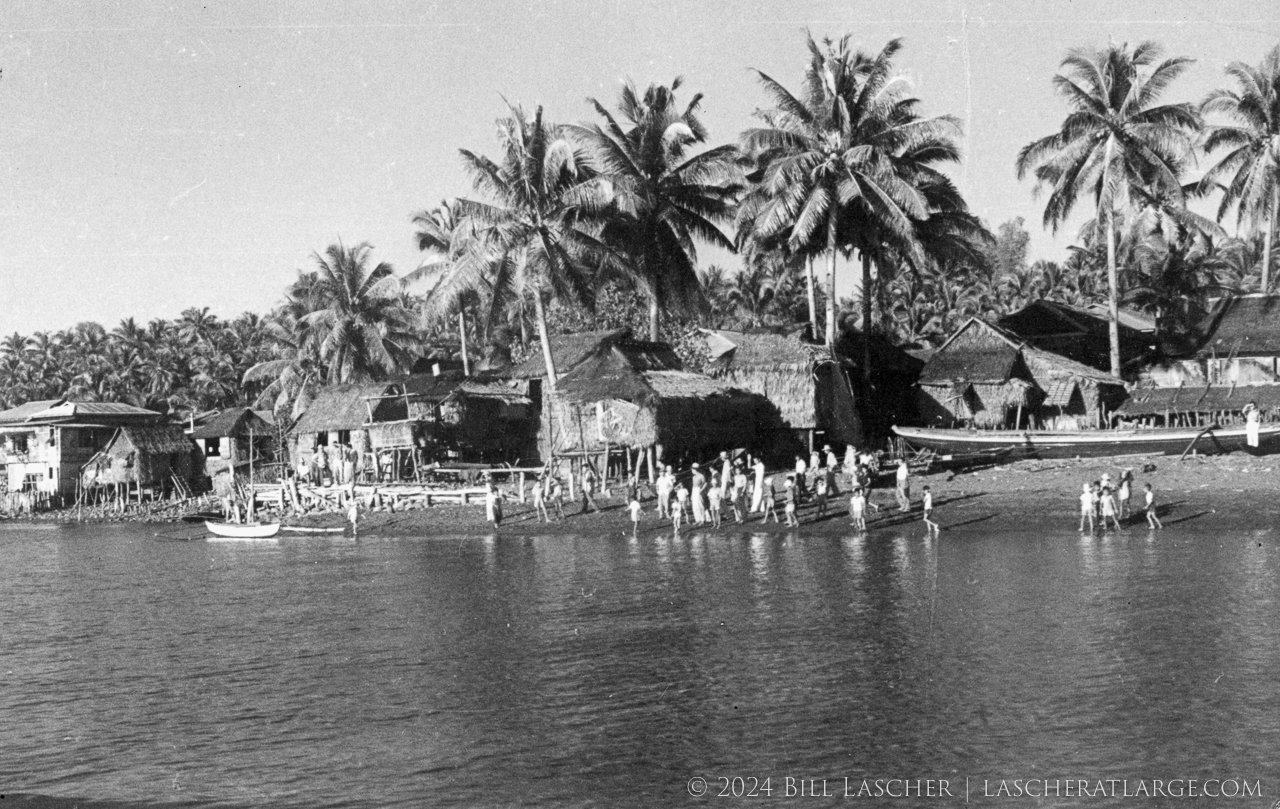

Philippine villagers on the shore

Residents of a village somewhere in the Philippines (likely Pola, Mindoro Oriental) watch from a beach as passengers of the freighter Princessa de Cebu escaping from the fortified island of Corregidor sail to shore. Among those escapees were Mel and Annalee Jacoby

Our contemporary world often feels fraught with hostility, fear, and tragedy. Sometimes I think the shadows darkening our time are akin to those that roiled Mel’s. Ideally, this volume will help illuminate a corner of the world as it was, as it is, and as it could be. There are others who can more precisely describe and interpret what happened in Asia (and elsewhere) during the period examined in this volume. This work admittedly interprets a recollection that has passed through three generations of my family’s memory and has been informed by my own professional experience as a journalist. It is not a removed, impersonal analysis. Even if it were, I didn’t experience the war, nor do I have direct connections to the cultures examined in this volume or the people who did.

Mel and his colleagues strived to accurately cover the war despite real threats and dangers. He risked everything to continue telling this story, he understood that doing so required professionalism, and he knew that expertise mattered because it strengthened value of the reports and images he and his peers recorded.

Aware of that intention as well as my own limitations, I have taken care to fairly and truthfully present these images in order to maintain that value. We must still fight to keep the story Mel helped tell visible and to retell it, even imperfectly, lest we risk repeating its darkest chapters.

Bill Lascher

September, 2023

Mel and Annalee in Uniform

Melville and Annalee Jacoby sitting together in a blacked-out hotel room somewhere in Australia (likely Menzies Hotel in Melbourne), April 1942, shortly after their escape from the Philippines aboard a blockade runner. Each wears uniforms issued by the U.S. Army to accredited correspondents, as indicated by the embroidered “C” visible on Mel’s shoulder. Annalee, then a contributor to Liberty Magazine, was the first woman accredited by the army in the Pacific Theater. Mel was Time Magazine’s Far East Bureau Chief.