Shanghai Takes it On the Chin

“I hate to see the rich kids in the cabarets, I hate to see the refugees, I hate to see the lousy foreigners in Packards and minks. Lots of money is being made now on the market and in business—but the Chinese peasant is taking it on the proverbial chin.”

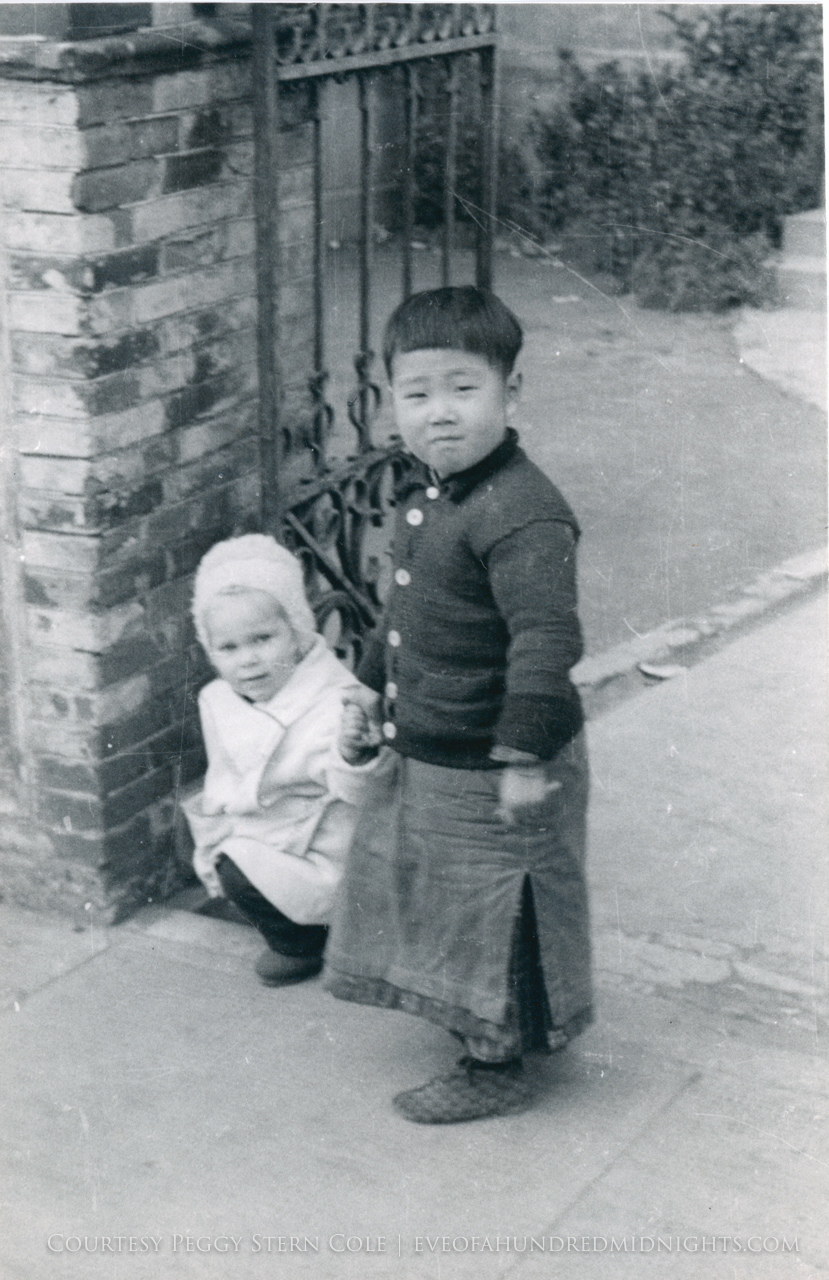

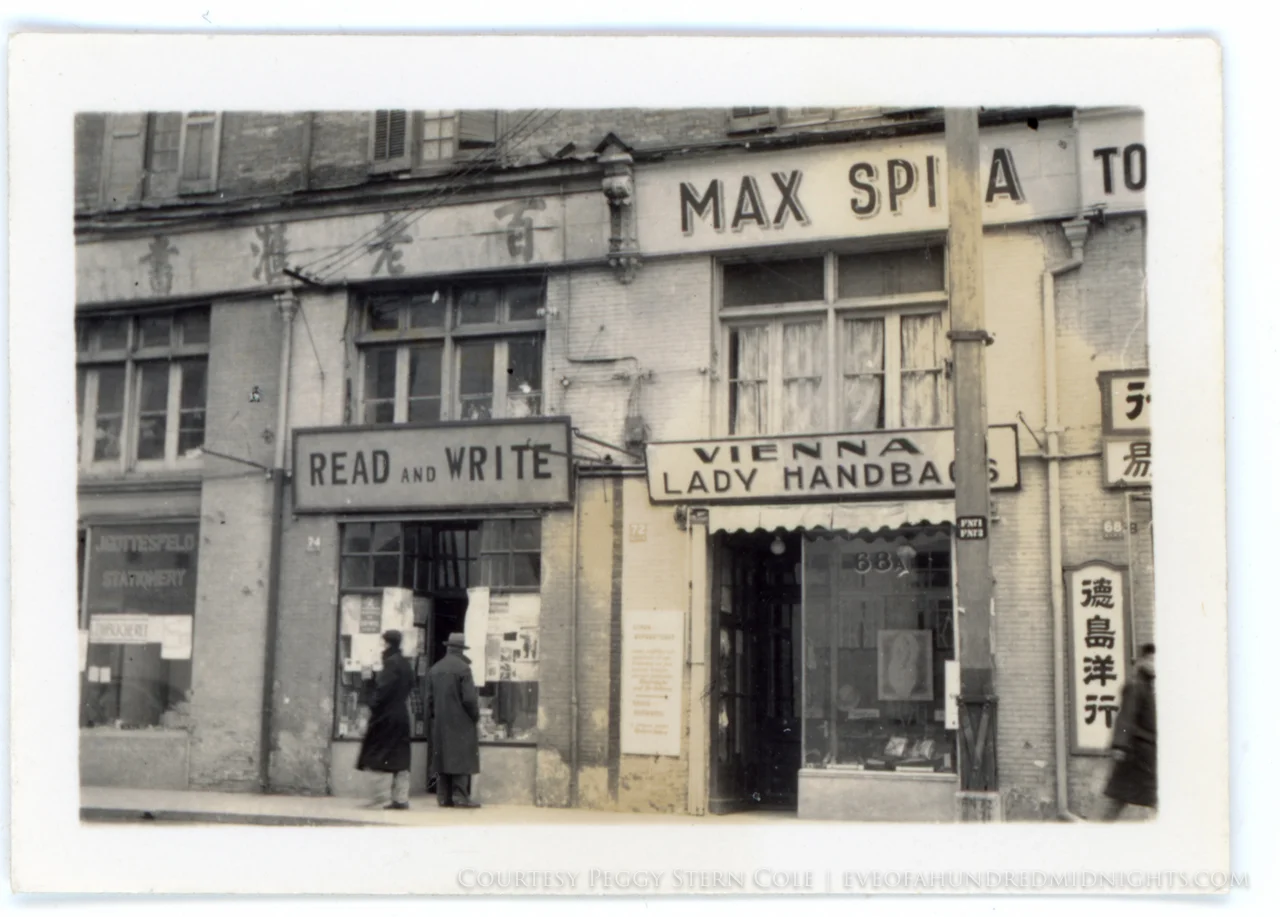

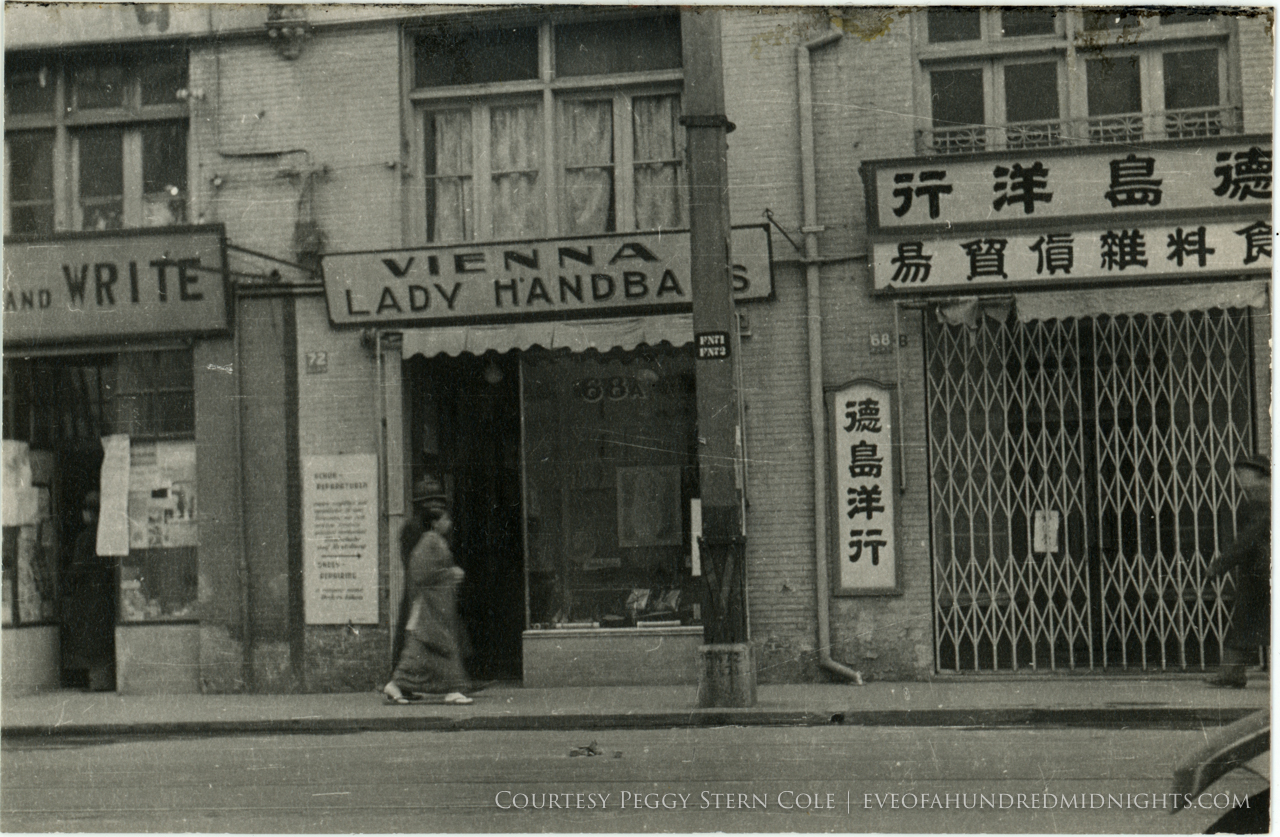

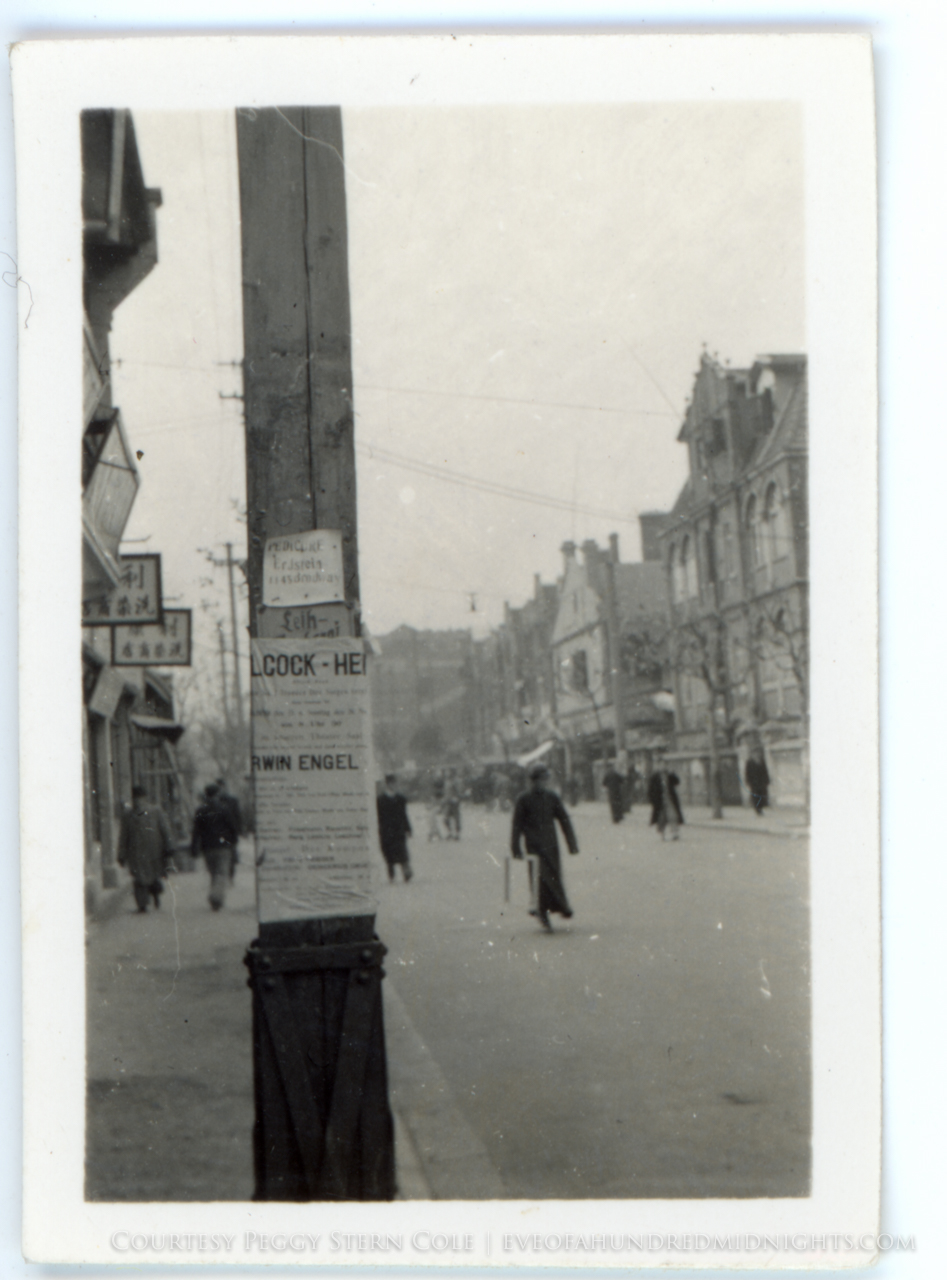

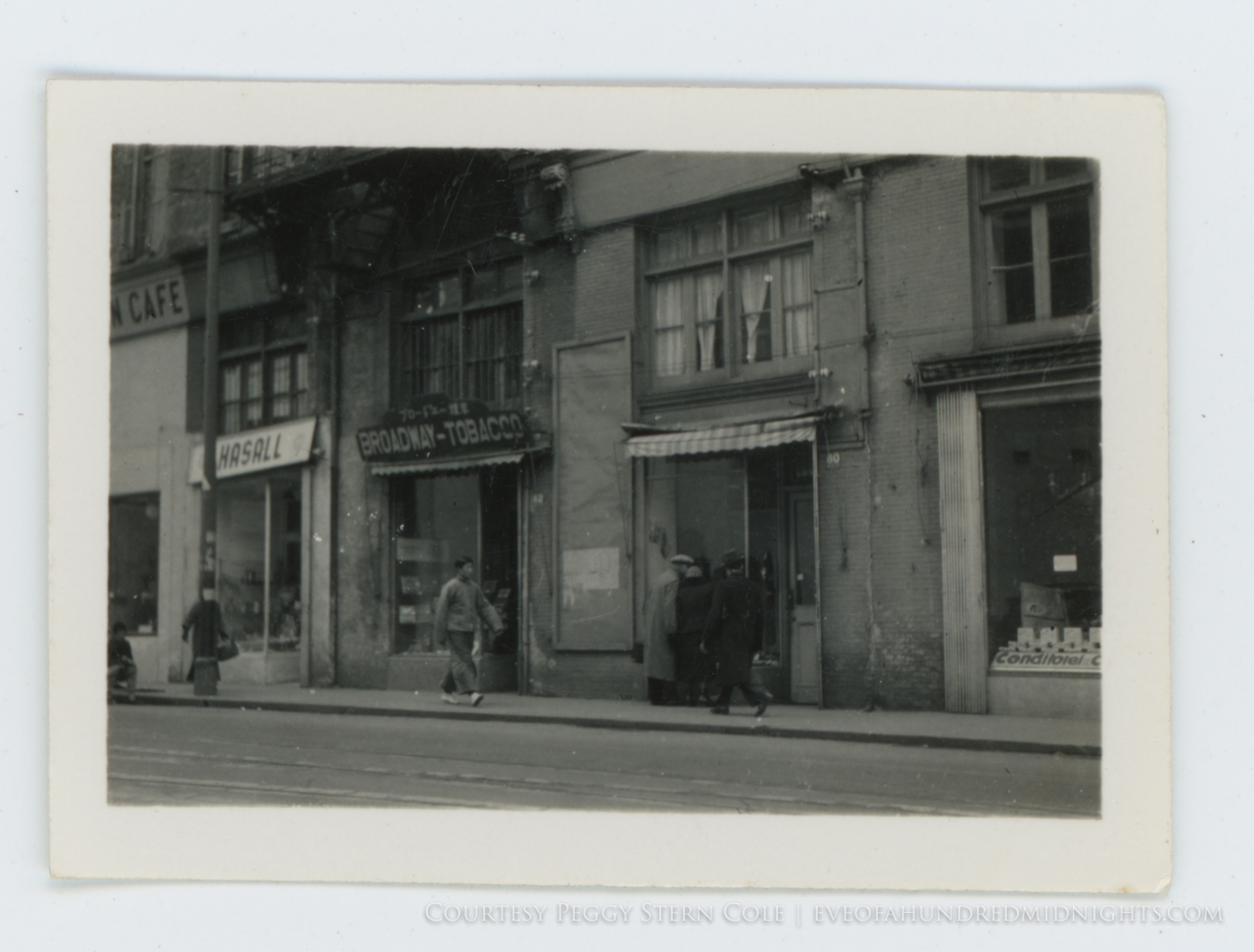

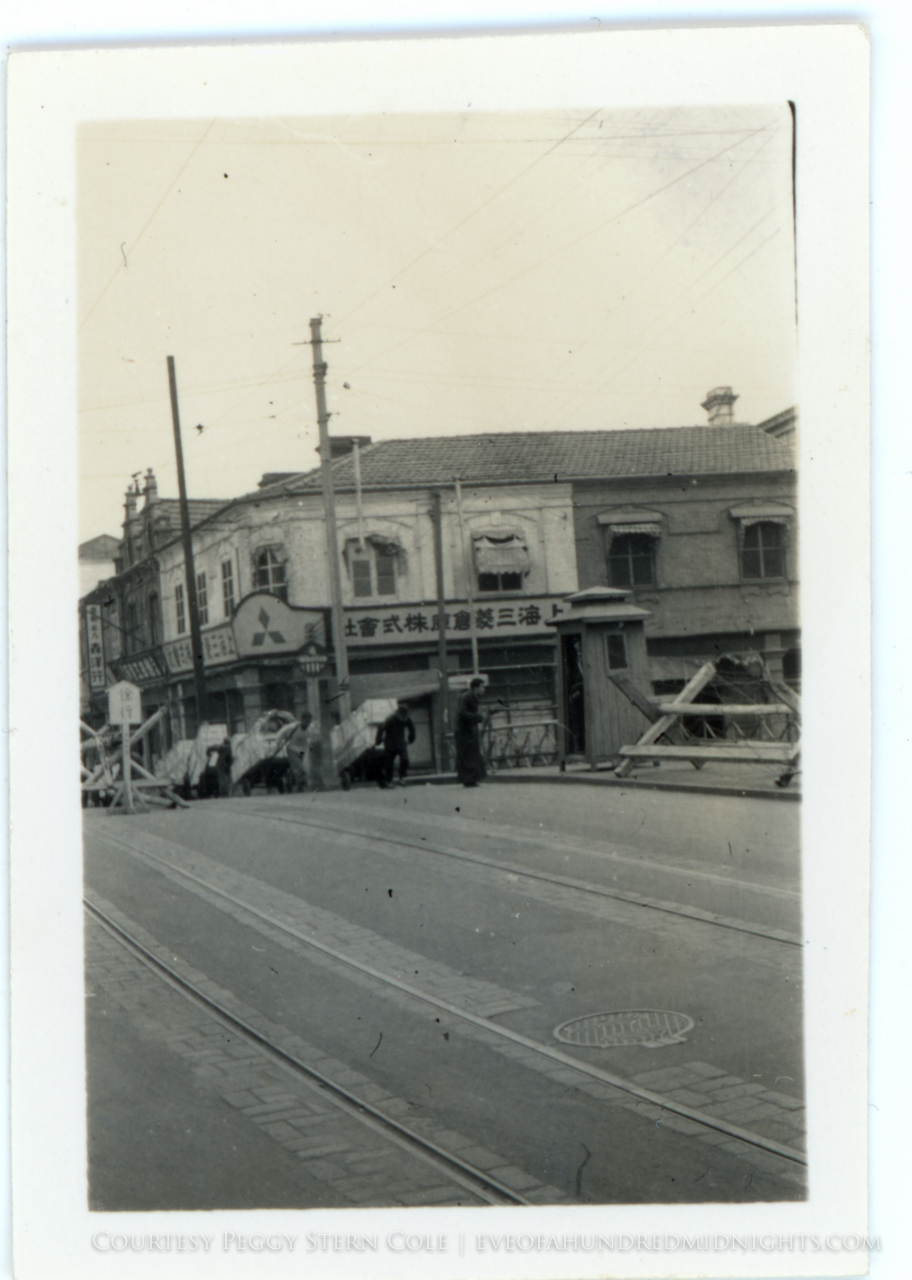

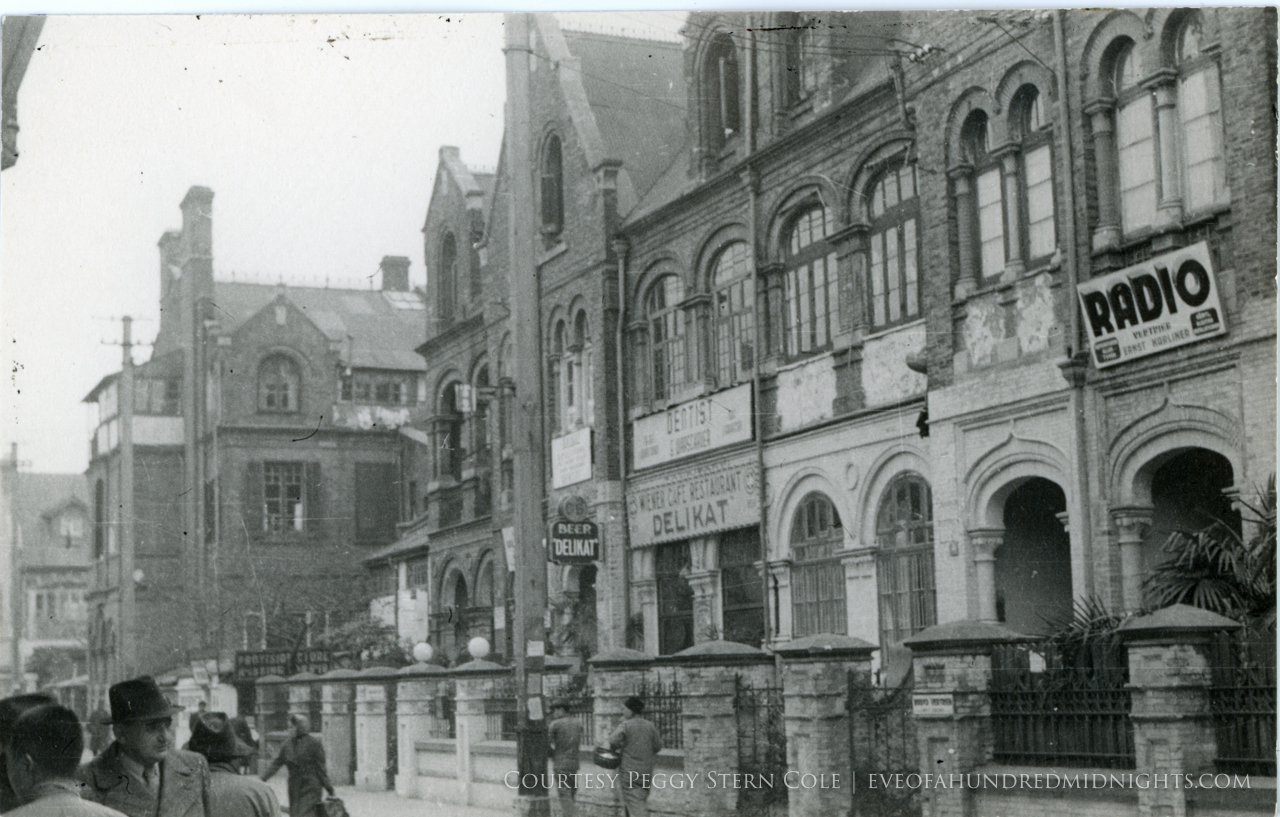

In November, 1939, Melville Jacoby arrived in Shanghai, China. Having just earned his master's degree in journalism from Stanford, Mel returned to China two years after studying there as an exchange student. Mel arrived in Shanghai with no work, but a raft of letters of recommendation from newsmen and scholars who had been impressed by a presentation Mel made of his research into California newspapers' coverage of China and Japan in the run-up to a war that had been raging since the summer of 1937, just as Mel completed his exchange year. As Mel hunted for work in Shanghai, he discovered a city packed with thousands of Jewish refugees who'd been turned away by every other port on Earth. It was a city occupied by Japan, though still nominally internationally-controlled, as it had been for decades. Here are some selections of how the city looked to Mel:

Here's how I described Mel's impression of Shanghai in Eve of a Hundred Midnights:

“But if you aren’t British or French or American or if your country hasn’t got enough gunboats it isn’t so international,” Mel wrote, referring to the many foreigners who came to Shanghai butwere not nationals of countries that enjoyed extraterritorial powers. Paradoxically, among the most disenfranchised populations in Shanghai were Chinese nationals. And though Shanghai maintained much of its international identity when Mel arrived in 1939, in the two years since the Battle of Shanghai, Japan had consolidated power there and grown increasingly belligerent toward both the Chinese and Westerners.

“The Western world is being squeezed out of China,” Mel wrote. “Their last opening wedges—the foreign concessions—are fastly becoming subject to Japanese pressure.”

Even as the Japanese took over, Mel found Shanghai society distastefully out of touch. When he went to exchange money at the American Express office, the bright blue travel pamphlets inside always seemed disconcerting to him, especially when a stretch of cold nights hit Shanghai and he saw humanitarian workers piling the bodies of Chinese laborers who had frozen to death into their trucks. Shanghai, the people in it, and the way the local Chinese were treated strained Mel’s patience to the point of anger. He said as much in one form or another in most of his letters.

“I hate to see the beggars (I’ll see millions more),” he wrote. “I hate to see the rich kids in the cabarets, I hate to see the refugees, I hate to see the lousy foreigners in Packards and minks. Lots of money is being made now on the market and in business—but the Chinese peasant is taking it on the proverbial chin.”

Bombing Season

Three quarters of a century ago, today, at the height of “bombing season,” World War II correspondent Melville Jacoby took a brief break from his radio broadcasts for NBC, his writing and photography for Time and Life magazines to write to his mother and stepfather about life in wartime Chungking, or Chongqing, then the capital of China.

Three quarters of a century ago, today, Melville Jacoby took a brief break from his radio broadcasts for NBC, his writing and photography for Time and Life magazines, and his chaotic search for a panda -- yes, a panda -- to write to his mother and stepfather about life in wartime Chungking, or Chongqing, then the capital of China.

Though the two-page letter was heavy with detail, Mel apologized for not writing more.

"Please say hello to the family for me," he wrote. "I just can't possibly write now. Perhaps a little later after bombing season."

Bombing season. Think about that for a second. A time of year when enemy bombers were such a regular sight overhead that you never fully unpacked from air raid evacuations. You became used to the idea that an air raid will regularly interrupt your day, as if it's an inconvenience like the 4 p.m. Southern Pacific train that slows your commute. You reach a point when you can't help but be reminded of bombs even when there aren't enemy planes overhead, as Mel did every time he fell asleep in Chungking's Press Hostel:

"I can see the sky from my bed quite clearly, but we call it home," Mel wrote of the compound where many foreign journalists lived and worked together. It was an uncomfortable home, one that a shift in Japanese tactics made less comfortable by the day, but it was still home.

For more about Melville Jacoby, wartime Chungking, and life in the Press Hostel, check out Eve of a Hundred Midnights.

A (Not So) Tiny Letter

I've been reading a lot of letters. It seems all I do these days is read letters.

But here's a letter for you. I wish I could send it to you on the onion-skin I so often find myself reading, the translucent sheets etched with the black ink of a an old Hermes's or Corona Portable's hammer-strikes, the sheet carefully folded into an envelope covered with bright stamps and decorated with a picture of a DC-3 and bold capitals reading "VIA AIR MAIL."

Of course, I can't, but I still want to say hello, because it's been a while (probably) and I miss you (certainly) and connecting beyond the superficial digital zones where we encounter one another. You may know where I've been, but perhaps something will settle on this screen. Letters, whatever their substrate, allow thoughts to steep better than ever-flowing streams of information we feel we must address and process now. Right now. Always now.

So feel free to read this and whatever letters follow at your leisure.

Hi,

I've been reading a lot of letters. It seems all I do these days is read letters.

But here's a letter for you. I wish I could send it to you on the onion-skin I so often find myself reading, the translucent sheets etched with the black ink of a an old Hermes's or Corona Portable's hammer-strikes, the sheet carefully folded into an envelope covered with bright stamps and decorated with a picture of a DC-3 and bold capitals reading "VIA AIR MAIL."

Of course, I can't, but I still want to say hello, because it's been a while (probably) and I miss you (certainly) and connecting beyond the superficial digital zones where we encounter one another. You may know where I've been, but perhaps something will settle on this screen. Letters, whatever their substrate, allow thoughts to steep better than ever-flowing streams of information we feel we must address and process now. Right now. Always now.

So feel free to read this and whatever letters follow at your leisure.

This Spring, while traveling between archives and libraries, first in Washington, D.C. and College Park, Maryland, then in Palo Alto and San Diego, I've had a sort of secondary education on the art of letter-writing. But what I want to discuss isn't what I've read in search of details about Melville Jacoby's life. I want to address what happens after processing so many diplomats' desk calendars, journalists' diaries, essayists' scrawled notes, and of course, the letters, those countless letters. I want to address what happens when I leave the reading rooms and need to unpack myself into whatever crevices of the day remain. Hard as I may work, these trips acquire meaning through what happens in their margins. Even seemingly inconsequential after-hours moments counterbalance days crammed with research and mountains of paper.

After I finished my first day at the Library of Congress, a college friend I hadn't seen since graduation showed off the senate office where she now works. I later met her husband (and adorable dog) while staying as the first overnight guest at the house they just bought. But what I remember from my visit wasn't catching up over what we've done the past dozen years, it was the three of us talking late into the night over meals and music, the kind of meandering conversation one remembers from college dining halls, dorm lounges and walks across the quad. In other words, the moments outside the classroom.

But for the bulk of my nights in D.C., I stayed on the couch of my best friend from grad school. We hadn't seen one another for half a decade. Because of a major event in the D.C. area while I was there, my friend, a TV news producer, was as busy as I. While we could only squeeze in a few hours of socializing, our familiarity with one another ran so deep that we didn't need to do anything to resume our patter after five years apart, and being busy together was our normal. Back at her apartment on the last night of my trip, we collapsed on the couch with wine, take-out and mindless TV. Both depleted by our work, the moment felt like the endless hours we'd spent agonizing over our Master's projects, commiserating over breakups and wondering what the hell we would do next with our lives. It was the comfort of familiarity balanced against a week working ourselves sick (Literally; I went home with a cold).

Pain and Gain

Two weeks later, I was at it again in California. There, I met friends' boyfriends at ballgames and high school classmates' babies at coffee shops. One night in L.A., after mingling with Tyrannosaurs and dancing among the imagined landscapes of a prehistoric Golden State, one of my oldest friends and I stretched the night deep into the morning, remembering youthful exploits on late nights long past.

On my second day in San Diego, after exhausting the collection I'd come to scrutinize, I visited the studio of an aunt literally working herself raw finishing a glass art installation. With my uncle explaining the painstaking preparations they were making to hang the work, my aunt stepped away from shaping a sea-green sheet of glass. She explained how, despite torn-up hands and her exhaustion, she was fulfilled by the work and grateful for the chance to involve the man she loved with its preparation. Toil doesn't only happen from nine-to-five, and it doesn't only happen in offices or construction sites.

Just the previous night, I met a high school friend I hadn't seen since 2001. Over cocktails and a late-night tea, we dissected the writing life, its sharp edges, and the truth of just how brutal our passions can be.

"Because I love making art, and I love being alive, I am trying to be brave, to be honest, and to listen carefully," she confided the next day in a North American Review essay. She felt like I sometimes do, like she was failing. "And so far this year, interestingly, it’s been the perfect fail. All pain, no gain."

Candid admissions were the order of the week. After my visit to my aunt's studio I met one more person, an old colleague who became a close friend years after we worked together. At a coffee shop near her childhood home we discussed "light" topics: books, TV shows, our families, etc.; but we also talked about her pancreatic endocrine cancer — and its often debilitating treatment. That afternoon, Huffington Post ran a piece she wrote originally for Reimagine.me about fighting to stay afloat financially. Years into her diagnosis, she hasn't even reached her 29th birthday. As she details in the piece, she didn't choose the expense of having cancer the way we make other informed choices about our major financial commitments, but she must bear it. I know her to be an artist as well, and I know that she is brave, and I know that she is honest about when she cannot be brave, and I know she listens carefully, and I even know much of what she loves about being alive. And I also know about her pain — though it's a real pain whose dimensions I can't fathom — pain that, by contrast with what art has brought my high school friend and I, didn't result from any of her choices.

Seventy-Two Years

Fortunately, pain isn't the only experience that catches us off guard. The previous night, I stayed late at UCSD's Theodore Geisel Library. On the bus to meet my high school friend, a woman who works at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies sat down next to me. We started talking about her research into genomics, as well as mine into history and wartime news coverage, and our mutual bliss throwing ourselves into work we love. It was one of those serene moments of connection, where as draining as our day had been, we regretted when the bus reached my stop, because it meant we couldn't continue this unexpected conversation.

But I learned one thing: Her name was Shelley. Shelley's name was easy to remember. My aunt with the glass-torn fingers is named Shelley. One of Mel's best friends was named Shelley. That day, I'd spent much of my time reading letters written between that Shelley (along with her husband, Carl) and the couple whose papers I was studying.

It's a coincidence, to be sure, but it was enough of one to get my attention. And it's on my mind again tonight.

When Japan invaded the Philippines, Mel and his wife, Annalee, escaped. But Japanese troops captured Shelley and Carl and imprisoned them with other American civilians. A few months after Mel's escape, he radioed Washington D.C. and urged U.S. officials to arrange a prisoner exchange, hoping his friends could be released. The government couldn't make the exchange happen, at least not then, but in a letter acknowledging Mel's request, his contact expressed relief at his and Annalee's safety.

"One of these days we shall hope to see you again," read one line of the letter, dated April 28, 1942.

I realize not only that this letter was sent exactly 72 years ago, but also that its hope would never be realized. Just a few hours later — indeed, nearly at the exact hour I finished the last edits on this letter — halfway around the world, an airfield accident would change everything, and kill Mel.

I hadn't intended to write this note to mark the anniversary of Mel's death, but I can't ignore that timing.

There's something else I can't ignore. Mel didn't choose his pain, either. He didn't have a chance to reconnect over the decades with old friends for drinks or dinners or candid admissions. Mel didn't have hours or days, let alone years, to recover from exhausting work. He only had his short life.

While I was working at the Hoover Institution, I went to an evening forum at Stanford's School of Journalism sponsored by Rowland and Pat Rebele. There was a reception after the talk, and I spent a long time there chatting with Rowland, whose curiosity about Mel's story deepened with each question I answered. That was exciting enough, but my biggest memory of the night was when I stood up from the panel discussion and noticed glass-encased shelves lined with cardinal-red, bound volumes. The spine of a book on the shelf closest to me read "An Analysis of Far Eastern News in Representative California Newspapers, 1934-38." It was a masters thesis authored by Charles L. Leong and Melville J. Jacoby. Of course I knew about its existence already, but seeing it there, moments before meeting Rebele, reminded me that I am doing the work I need to be doing, when I need to be doing it.

It's not news that writing is a solitary existence. Since I am single, and I work from home, and I don't have roommates, I sometimes feel even more isolated. All these moments of connection these past months, however, make this work feel far less lonesome. Indeed, they reminded me that there are people who understand the work I'm doing, even if miles, years and conditions separate us.

That's part of the reason I'm writing you; in the past, you've shown an interest, and I want to carry on whatever conversations we've already started, or begin ones that might last into the future. I'll write occasionally to this list; sometimes once a week, sometimes a little more or a little less frequently; sometimes longer, sometimes shorter. Yes, I want to keep you interested in my book, but I also want to experiment with a simple but elusive concept: getting and remaining in touch. If this isn't the place for you to do that, or you don't want to remain in touch, please don't feel obligated to do so and please don't feel like you'll offend me if you unsubscribe.

But that's why I'm writing you today, and if you can, and if you want, write back when you can, about this, about your passions, about anything. And share this note widely with people who'd want to read it, and who'd want to be part of the conversation.

-Bill

P.S. If you want to keep track of what I have to say but don't want to subscribe, please consider a visit to my blog, follow me on Twitter, Tumblr or Instagram.

Paying the Price for a Smoking Gun

By the time I had the confidential State Department documents in my hands, I was five days into my research trip to Washington, D.C., I'd flipped through hundreds, maybe thousands of pages of dusty, sometimes crumbling government documents, private letters from publishing luminaries, and even water-stained diaries from hungry, stranded soldiers unaware of a coming death march through mosquito-infested, sweltering jungles.

Now I need your help to keep looking.

By the time I had the confidential State Department documents in my hands, I was five days into my research trip to Washington, D.C., I'd flipped through hundreds, maybe thousands of pages of dusty, sometimes crumbling government documents, private letters from publishing luminaries, and even water-stained diaries from hungry, stranded soldiers unaware of a coming death march through mosquito-infested, sweltering jungles.

All of it was fascinating, but more than halfway through my trip, little of what I'd found was of use to me. I'd spent nearly every dollar I had to travel to the National Archives and the manuscript division of the Library of Congress, and I still hadn't found a smoking gun. I needed something that would allow me to triangulate Melville Jacoby's position amid all the myths and memories of World War II that have bled into our consciousness over three quarters of a century.

I'd ended the previous week sifting through a slender box containing thousands of typed index cards. They mapped the paper trails of countless other lives who'd crossed paths with U.S. diplomatic officials at the height of World War II. As the day drew to a close and I began to crumble — I'd barely slept for a week, rushing first thing every morning to the repositories and staying until librarians forced patrons to leave — I saw Mel's name.

I pulled the card, somewhat surprised to learn it led to a "confidential file" from 1942. I'd fantasized about discovering once-secret documents related to Mel, but knew I could have been over-romanticizing his life. It wasn't the only card I found. There was another, more somber file indexed. Beneath a bureaucracy of typed decimal reference numbers read the title "Death in Australia of Melville J. Jacoby, American Citizen."

It would be three more weeks — indeed, yesterday morning — until I received a copy of that file, but in truth, I already know perhaps more than I want to know about Mel's death. What I sought at the archives that week was more of his life. That Monday morning, the stack of telegrams that began with a blaring all-caps "CONFIDENTIAL FOR TIME, INC., WITH MY APPROVAL, FROM JACOBY," sent by Francis B. Sayre, the U.S. High Commisisoner for the Philippines, was a treasure.

In time I'll unveil why what was within mattered, but I'm bringing it up now to explain that the find didn't come easily, nor cheaply, nor does it mean I'm done working. Today I leave for California and visits to two university special collections, and I need your help more than ever. Can you spare a few dollars so I can keep searching for history?

Here's a breakdown of what I'm spending and why I need your help:

- $836.56 — Amount spent for a round-trip flight from Portland to Washington, eight days of food and Metro fares, but mercifully excluding lodging, thanks to three terrific hosts.

- Emptied — The Amtrak Guest Rewards balance and Southwest travel credits I used for travel between Portland, San Diego and Palo Alto for a second, 15-day-long trip beginning today.

- $720 — Approximate combined total of expected food, transportation and other research-related expenses over the next 15 days.

- [Redacted] — Current abysmal balance of my savings account, especially following today's rent.

- $380 — Total amount I've received in contributions to support research travel this Spring.

- None — Outside income expected from freelance writing and editing clients during my trip.

- $1177.56 — Amount I still need just to break even for this trip.

- Priceless — The generosity of six households inviting me to stay during portions of each trip, thus saving me from paying for three weeks of lodging.

When I wrap up this second trip, I will have spent the better part of five weeks searching for Mel's story in the haystacks of archives and special collections libraries. That also means five weeks travelling, pulling documents, sifting and reading them, taking notes, processing what I've found, all on top of time I've been spending drafting new chapters of my book, revising my proposal and further developing my platform (That's also five weeks without time to report or research other paying stories, apply for outside jobs, or seeking alternative funding).

Why This Matters

Writing nonfiction is as much an archaeological dig as it is a creative endeavor. Sure, if I want to bash my keys into the form of a story, I can assemble a thin skeleton resembling Melville Jacoby's experience. As that comparison implies, such an outline would lack life.

It turns out that aside from my trip to California I'll have to go back some day to the National Archives. Five days split between there and the Library of Congress were too few to process the hundreds of files that contain relevant documents. Now I know where to target my next search, but I'll need to return to the archives to conduct it.

In the past three weeks I've also confirmed that there once existed a film of Melville and Annalee Jacoby's last kiss. I know who shot the film, though I do not yet know whether it has survived the decades. It may very well rest in an archive somewhere, but I'm going to need your help to find it.

But as much as this dig matters to me, what does it mean for you? What do you care if I find some record detailing the tonnage of the boat Mel rode through the Philippines 72 years ago? Why should you be interested in him, particularly given that it will probably be a while before you read much about him (but don't miss this story in which he makes a guest appearance)?

Perhaps it's the mythic nature of this story: Given a choice between following his passion straight through danger and uncertainty or a secure, but unchallenging, career move, Mel chose to leap. In doing so, he not only connected with his eventual wife, Annalee, a woman making a similar gamble in pursuit of her passions, but found a job far more promising than the safe opportunity he'd sacrificed. With the world erupting in flames around them, Mel and Annalee's lives intertwined. Together, they braved great danger to chronicle the horrors around them. Finally, after a tremendous escape and much sacrifice, they reached a serene, peaceful refuge, where home beckoned and nothing seemed capable of going wrong ...

This is a grand story of a world teetering on the precipice of historic upheaval, an intimate tale of two young people with the world laid out before them, and a glimpse of moments of tenderness they're able to share amid the harshest circumstances.

While I find this story compelling, it's possible that's not what will motivate you to offer a few dollars. Might there be other reasons you'll contribute? Have I ever entertained you? Were you ever intrigued by something I've written or said elsewhere? Did you ever laugh at one of my tweets or status updates. Was I the one to introduce you to my neighborhood goats? Has their been a reporting trend you found out about or an under-discussed natural danger you've learned about because of me? Maybe I helped you discover a new way to get around your city.

I wonder whether there's something more personal that might convince you to support me. Have I ever introduced you to a new friend or helped you find a lover? Perhaps we've cheered for the Dodgers together. Maybe we took a class together, or whiled away a few hours over beers. Did we run miles and miles together? What about traveling; have we crisscrossed the country or explored a foreign city together?

Maybe we've held each other's hands. Maybe we've kissed. Maybe we've fought.

Perhaps we've cooked a meal together or whiled away a Sunday morning at brunch. Perhaps we've stayed up dreaming, regretting or reminiscing. Perhaps I witnessed your wedding or watched your children grow up. Perhaps I celebrated your career and cheered your triumphs.

Maybe you once sat in awe listening to Mel's tale and told me who should play the leads in a movie of this life, wondering why no publisher has picked it up yet, let alone a film studio.

There's another potentially more likely possibility: we may have never met. It's quite likely we've never shared anything beyond existence in this moment. But maybe you recognize something in these words, some kind of yearning for it all to finally click, for something to come of years of work.

Maybe you don't want to give me anything. So, I wonder, what would you suggest? What should I do to keep these wheels turning? Where do I find work that I can pour myself into while still being able to tell Mel's story? How can I fund that story? What am I missing?

My Own Worst Enemy

Oops.

In an ideal world, this blog post would be an update about all the amazing things I discovered while perusing the radio broadcast transcripts housed at the University of Oregon. Unfortunately, that wasn't to be.

Oops.

In an ideal world, this blog post would be an update about all the amazing things I discovered while perusing the radio broadcast transcripts housed at the University of Oregon. Unfortunately, that wasn't to be.

I woke up early Saturday, excited to make my first foray into the field researching Melville Jacoby's story (not counting my visit to the shipwreck named after him, or the informal visits to my grandmother's house work on this project began in earnest). The drive was pleasant. Eugene was lively as students and visitors enjoyed the sun and warm temperatures. The special collections librarian on duty was helpful and welcoming, as was the undergraduate assistant who lugged up a huge box of transcripts to the collection's reading room.

It looked like she was in for many more trips. There were nine total boxes, and it wasn't clear what order they were in. There was no finding aid, so I'd have to guess.

So, I started with box number one. It kinda felt like christmas as I opened it. What might I learn? What might I discover inside?

Folders and folders and folders full of typed and mimeographed documents. Many were on Republic of China letterhead. Most addressed Charles Stuart, the dentist in my home town who'd received the broadcasts Mel set up. The earliest was dated 1943. Uh-oh...

You see, Mel died in 1942 (indeed, I was at the library just a day short of the 70th anniversary of his death). Somehow, every time I'd read the index citing the collection I'd read it as containing all the records connected to XGOY since 1939, when Mel had helped arrange the station's linkup with the U.S. It turns out the collection was only partial, and the correct dates were even in my notes. How had I processed it so incorrectly? Wishful thinking fueled by my eagerness to finally get some meaty research done, maybe?

Though this reinforced my need to travel to other archives and personal collections it does make me wonder where the first half of these materials are (though it's still not really clear why any of them are in Oregon -- the librarian at the U of O thought it might be because some missionaries have contributed other materials to its collection). But that's part of the fun of all this: tracing all the bread crumbs I might find and answering all the questions connected to the fascinating life of Melville Jacoby.

Anyhow, such errors are bound to cross my path occasionally. I've written previously about my mistakes. All I can do is move along and keep working.

Mailing List

Meanwhile, if you're interested in keeping tabs on this story and more from me consider signing up for my mailing list.

Oh, and don't forget to contribute.

Studying Melville Jacoby in Eugene

Many of you have heard about Melville Jacoby by now. Those who haven't can read more about him there, and elsewhere on my blog. Now that the seventieth anniversary of his death is upon us, I'm renewing my work writing the book Mel never got to write.

Later today I'm headed down to Eugene, OR, to visit the special collections at the University of Oregon library. There, I'll peruse the manuscripts of the Charles E. Stuart Collection. Stuart, you'll recall, was the dentist and amateur radio enthusiast in Ventura, Calif. who received radio broadcasts Mel set up from XGOY, the official Republic of China radio station in wartime Chungking, China (now known as Chongqing).

Many of you have heard about Melville Jacoby by now. Those who haven't can read more about him there, and elsewhere on my blog. Now that the seventieth anniversary of his death is upon us, I'm renewing my work writing the book Mel never got to write.

Later today I'm headed down to Eugene, OR, to visit the special collections at the University of Oregon library. There, I'll peruse the manuscripts of the Charles E. Stuart Collection. Stuart, you'll recall, was the dentist and amateur radio enthusiast in Ventura, Calif. who received radio broadcasts Mel set up from XGOY, the official Republic of China radio station in wartime Chungking, China (now known as Chongqing).

Many of you have heard about Melville Jacoby by now. Those who haven't can read more about him there, and elsewhere on my blog. Now that the seventieth anniversary of his death is upon us, I'm renewing my work writing the book Mel never got to write.

Later today I'm headed down to Eugene, OR, to visit the special collections at the University of Oregon library. There, I'll peruse the manuscripts of the Charles E. Stuart Collection. Stuart, you'll recall, was the dentist and amateur radio enthusiast in Ventura, Calif. who received radio broadcasts Mel set up from XGOY, the official Republic of China radio station in wartime Chungking, China (now known as Chongqing). Somehow, the complete transcripts of these broadcasts, files full of related materials and original recordings of them ended up just 100 miles away from my current home. Though my grandmother has a few of the recordings, I've yet to visit her home in California to listen to them since this project started.

Many of you have heard about Melville Jacoby by now. Those who haven't can read more about him there, and elsewhere on my blog. Now that the seventieth anniversary of his death is upon us, I'm renewing my work writing the book Mel never got to write.

Later today I'm headed down to Eugene, OR, to visit the special collections at the University of Oregon library. There, I'll peruse the manuscripts of the Charles E. Stuart Collection. Stuart, you'll recall, was the dentist and amateur radio enthusiast in Ventura, Calif. who received radio broadcasts Mel set up from XGOY, the official Republic of China radio station in wartime Chungking, China (now known as Chongqing). Somehow, the complete transcripts of these broadcasts, files full of related materials and original recordings of them ended up just 100 miles away from my current home. Though my grandmother has a few of the recordings, I've yet to visit her home in California to listen to them since this project started.

With the visit timed to the anniversary of Mel's death, I'd hoped to hear his voice for the first time. Alas, that won't be possible, as the recordings are too fragile for the university to allow me to play them. I'm told the archives can't play the recordings until they're digitized — they're so fragile that even playing them once could damage them beyond repair. I completely understand the precaution. Unfortunately, it's not clear to me when the recordings will be digitized as they're not a high priority for the university. If I want to hear them I'll either have to find a way to collaborate with the school to digitize them or find other sources for the recordings. Meanwhile, I'll have to further hasten plans to listen to those recordings my grandmother has, but fragility will be an issue there, too. Your support will help make listening to (and digitizing) these recordings possible, and pays for research like that I'm about to conduct in Eugene.

Despite not being able to listen to the recordings, I'm excited for the visit. The manuscripts will provide a detailed look at Mel's working life, the events taking place in China immediately surrounding him, and the people with whom he worked and interacted. I'm eager to take the trip, and thankful that the support I've already received has made it feasible. I'll be sure to keep you up to date on what I find out and where I go next.

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4

![Restaurant Rosenthal With Bike in Foreground [Good shot] Shanghai.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51db1d79e4b03e2f06324d97/1473379937704-QU4YB2Z2NR49I06U7QDN/Restaurant+Rosenthal+With+Bike+in+Foreground+%5BGood+shot%5D+Shanghai.jpg)