A Selection from The Golden Fortress

A CLOUDLESS SKY BLANKETED ALTURAS as a string of sedans turned off Highway 299.

Temperatures that afternoon had briefly crept above freezing but dipped again as dusk arrived. From atop a three-story brick building at the other end of Main Street, the word HOTEL blazed against the cloudless sky. On an evening as clear as that one in early February 1936, the beacon of the signage must have been a welcome sight to the cars’ occupants as they drove those last three blocks from the highway to the Niles Hotel, hundreds of miles, two days, and a world away from home. That those last three blocks also composed the entirety of downtown Alturas said everything about how far they’d traveled.

After the men parked their cars, they might have reflexively shivered beneath their polished leather jackboots and thought of the all-year warmth and sun they’d left behind. If any of the men passed beneath the street lamp at the corner of Modoc and Main Streets, its glow might have glinted across the gold-toned badges they carried, illuminating an eagle’s wings spread above the words POLICE OFFICER and LOS ANGELES typed in blue lettering beneath, and the embossed seal that read, CITY OF LOS ANGELES. FOUNDED 1781.

The following excerpt comes from Chapter 1 of my latest book, The Golden Fortress: California’s Border War on Dust Bowl Refugees, published Aug. 9, 2022, by Chicago Review Press. If you’d like to read the rest of the chapter, and the book, I have a limited number of signed editions available for purchase here, or you can order the book from Bookshop or your favorite retailer. The audio book is also available from Libro.fm and other sellers, and ebooks are available in EPUB, PDF, Kindle, Kobo, Nook, Apple Books and Google Play.

A CLOUDLESS SKY BLANKETED ALTURAS as a string of sedans turned off Highway 299.

Temperatures that afternoon had briefly crept above freezing but dipped again as dusk arrived. From atop a three-story brick building at the other end of Main Street, the word HOTEL blazed against the cloudless sky. On an evening as clear as that one in early February 1936, the beacon of the signage must have been a welcome sight to the cars’ occupants as they drove those last three blocks from the highway to the Niles Hotel, hundreds of miles, two days, and a world away from home. That those last three blocks also composed the entirety of downtown Alturas said everything about how far they’d traveled.

After the men parked their cars, they might have reflexively shivered beneath their polished leather jackboots and thought of the all-year warmth and sun they’d left behind. If any of the men passed beneath the street lamp at the corner of Modoc and Main Streets, its glow might have glinted across the gold-toned badges they carried, illuminating an eagle’s wings spread above the words POLICE OFFICER and LOS ANGELES typed in blue lettering beneath, and the embossed seal that read, CITY OF LOS ANGELES. FOUNDED 1781.

Once inside the Niles Hotel, thirteen Los Angeles police officers waited as their commanding sergeant, R. L. Bergman, checked them into the hotel. The next morning they would officially begin their new assignment here in the seat of Modoc County, six hundred miles away from the City of Angels. Somehow, despite traveling so far, the officers still hadn’t left the Golden State.

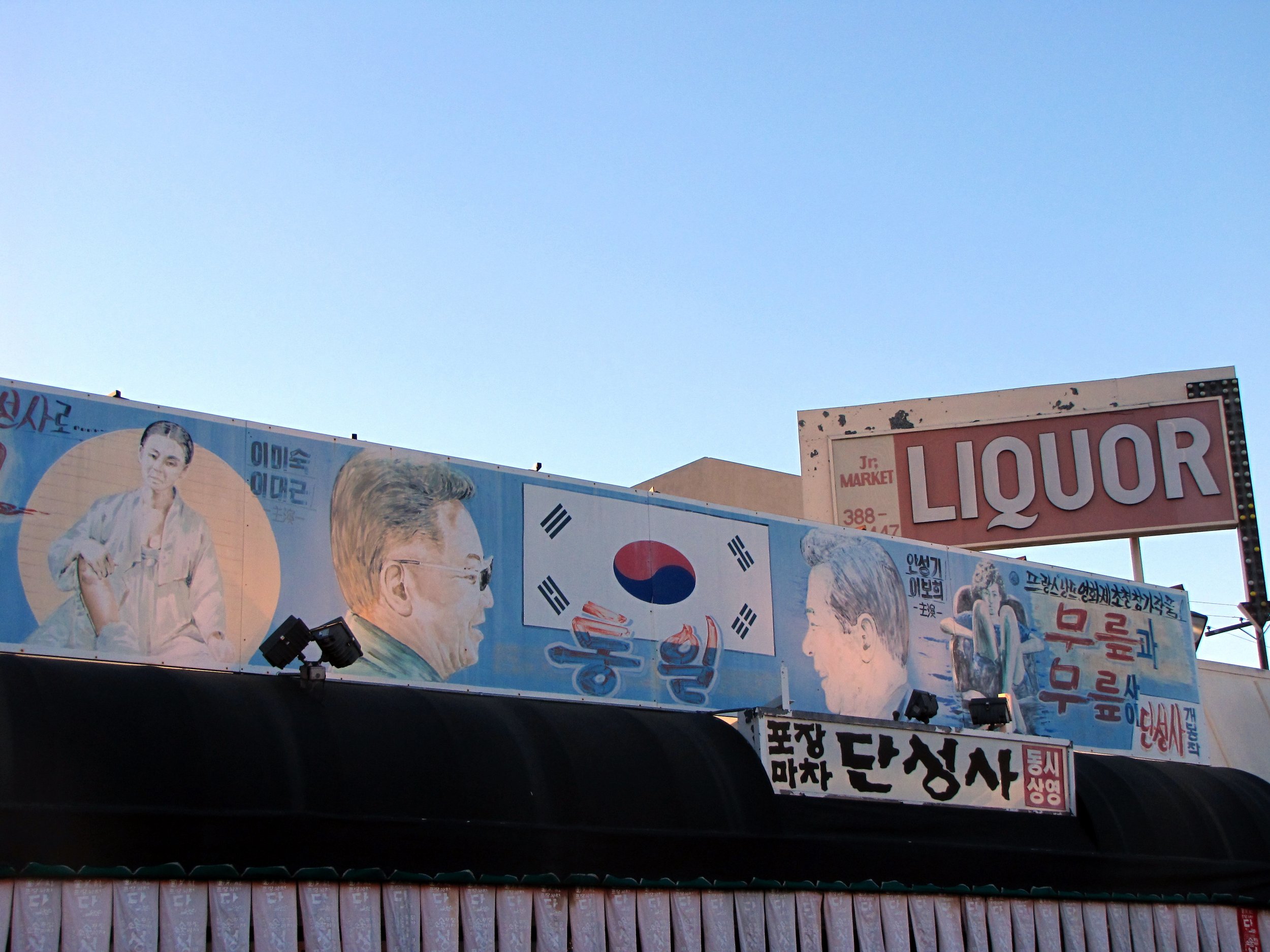

A cultural distance matched the physical distance. Alturas was Modoc County’s largest town and still remote from the nearest settlements of any size. The hotel was at the southern end of downtown, which ended a few hundred feet away at a small bridge over the gurgling Pit River. It was surrounded by the kind of businesses typical of a certain mythologized small town in the early twentieth-century American West: a coffee shop next door, a butcher down the block, a liquor store up the street, and an inn across Main Street with signage advertising BUFFALO BEER on tap. The county courthouse was just a couple blocks northeast of the hotel. A few businesses fronted East and West Carlos Street. The rest of the nearby streets were residential. The surrounding sparse, frigid, mostly undeveloped expanse where the men would work for the foresee- able future dramatically contrasted with the bustling, sun-bathed metropolis they’d left two days prior, but their task remained the same as it had been at home: protect and serve the City of Los Angeles.

Soon after the officers arrived at the Niles Hotel, a primly dressed woman walked in and introduced herself to Sergeant Bergman. She was Gertrude Payne French, the publisher of the Alturas Plaindealer. Could she just interview the sergeant for a little bit about why the police had come all the way to Modoc County from Los Angeles?

She could. Bergman knew how highly his boss, Los Angeles police chief James Edgar Davis, valued good publicity. And Homer Cross, Davis’s deputy in charge of crime prevention and this operation’s key architect, had softened the ground throughout the state in the weeks leading up to the deployed officers’ arrival.

French already knew why they were there, of course. Cross had talked to her when he came to Modoc County that January. Even if he hadn’t, French may have known, as she prided herself on how plugged in she was to events transpiring all across California. After all, she was one of the Native Daughters of the Golden West, a member of the Alturas Chamber of Commerce board of directors, and, like her husband, R. A. “Bard” French, a former operative in the state Republican Party. Gertrude and Bard were very encouraged, French told Bergman, that someone—Chief Davis—was finally doing something about the “penniless itinerants and criminals” plaguing the Golden State. Concerns about how out-of-town police might disrupt Modoc County were already spreading. The Plaindealer would diligently downplay these concerns on its pages, but, French told Bergman and would repeat in print the next day, the paper was “reserving our final judgment to see what happens.”

Whatever judgment ensued, numerous scenes like the one taking place at the Niles Hotel likely occurred throughout the remotest corners of California that evening. Davis had sent Bergman, the two seven-officer squads working under him, and 120 other Los Angeles police officers—each handpicked by the chief from a larger pool of volunteers—to seize control of the state’s borders. Each squad was stationed at one of sixteen entry points around the perimeter of California. Some would patrol highways and set up checkpoints to stop incoming cars, while others boarded trains to look for fare evaders and stowaways. All those entering California who appeared unable to support themselves and likely to become public charges or who the officers believed likely to be criminals would be stopped. No one was to get through without permission from the Los Angeles Police Department, even if Los Angeles itself was hundreds of miles away.

Los Angeles police chief James Edgar Davis and Los Angeles County superior court judge Minor Moore present Los Angeles mayor Frank Shaw with a Texas-shaped birthday cake on the eve of Davis’s rollout of his border blockade. Courtesy of Los Angeles Times Photograph Collection, Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Perhaps Chief Davis, originally from Texas, thought of the deployment’s launch as a birthday gift for his boss, Los Angeles Mayor Frank Shaw. That Saturday morning, Davis sat down with Shaw, not to celebrate his birthday but to discuss the blockade, just as someone wheeled a sixteen-pound birthday cake into the mayor’s office. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Minor Moore—also a transplant from the Lone Star State, and president of the Texas Society of Southern California—was the enormous dessert’s likely mastermind. Moore, who called Shaw to wish him a happy birthday just as the cake arrived, had conspired with Shaw’s Texas-born wife, Cora; his mayoral counterpart in Dallas, George Sergeant; and officials from the Texas Centennial Exposition, who actually paid for the giant confection.

As mayor and police chief, respectively, Shaw and Davis were among Los Angeles’s most prominent public figures. Before becoming mayor, Shaw, a grocery-chain executive and one of California’s wealthiest politicians, was a Los Angeles County supervisor who led the county board’s efforts to blame Los Angeles’s fiscal woes on poor, unemployed migrants. Davis, a former chief of police who’d been re-elevated to the position when Shaw was elected mayor, made arresting homeless and other visibly poor Angelenos a key plank of his policing strategy. Both men could trace their success in part to the city’s obsession with drawing tourists (and their money) while simultaneously shunning poor migrants (and their need). Like other California cities, Depression-era Los Angeles treated transients as little more than parasitic threats. Indigent relief was burden enough for these cities’ own residents, the argument went. Why should they pay for other cities’ discards?

Reliant as their public rhetoric might have been on antimigrant sentiment, neither Davis nor Shaw were truly of Los Angeles. Between fleeing his native Texas and arriving nearly broke in Los Angeles, Davis spent many of his early years as a drifter, while Shaw was born in Canada and grew up bouncing around the Midwest. Neither likely discussed those backgrounds when they met at city hall three days before Davis’s officers arrived in Alturas.

The day after their meeting, Davis put an exclamation point on declarations that outsiders—or at least, the wrong kind of outsiders—just weren’t welcome in the City of Angeles. Davis deployed his border patrol, confident in a full-throated endorsement from Shaw. The chief also knew he could count on support from the Los Angeles powerbrokers who helped elect the mayor three years earlier and who for years had decried what they believed were “hordes” of transient “ne’er do-wells” invading the city. Now well into his second stint as Los Angeles’s police chief, Davis had Shaw to thank for his job.

Whether Davis conceived the operation as a favor to Shaw or not, the fervor with which he pursued it was hardly surprising. He cared little about misgivings lawmakers expressed about earlier proposed anti-indigent and anti- migrant measures. He also had no qualms that his officers might trample a few constitutional protections in their attack on criminality and the vagrants who he believed embodied it.

And it would make sense if Davis believed he owed something to the mayor. At the outset of 1930 Shaw’s predecessor, John C. Porter, had demoted Davis from chief to deputy chief after a series of high-profile scandals involving his department. After Shaw replaced Porter in 1933, one of his first official acts had been to put Davis back in power. In return, Davis carefully crafted his police department to serve as the primary municipal tool to guard the free-market-cherishing, business-friendly forces cherished by Shaw and responsible for his election.

Amid the economic turmoil and labor unrest of the Great Depression, Davis—while also sparking the Los Angeles Police Department’s inchoate development into a paramilitary force that would serve as the national standard for militarized policing—reveled in using the department’s power to harass and intimidate union organizers, civil libertarians, and political progressives. Now, the chief turned his attention toward the wretched souls washing across California’s borders from barren Dust Bowl farms and Depression-shuttered factories. To hear it from the agenda-setting Los Angeles Times, the city’s chamber of commerce, and Davis himself, these domestic migrants, if not already criminals, were likely to become criminals given enough time loitering on the streets of Los Angeles.

Davis’s plan would neutralize that threat with a phalanx of officers at California’s borders ready to block incoming laborers while the rest of his officers scoured Los Angeles’s streets for indigent transients and “vagrants.” After months of preparation, the plan was finally ready. Beginning that Sunday, February 3—a day after Shaw’s birthday—and continuing into the following afternoon, squad after squad of officers piled into personal cars, drove past the city limits, and continued to the farthest reaches of California, where they would assume their duties as the Golden State’s first line of defense from the uncivilized masses beyond.

The Complete Incomplete Los Angeles Guide

Friends often ask what they should see and do in Los Angeles. This is always tough to answer because the city constantly evolves, as do my own tastes, and that doesn't take into account the unique preferences of the asker. Nevertheless, when a family of Austrian friends planned to stop in Los Angeles last summer, I compiled a list of suggestions based on their interests (seeing the beach, experiencing iconic architecture, and viewing landmarks). With a few changes and updates, I thought I'd share it with you.

Though I currently live in Portland, Oregon, I don't hide my love for the city of Los Angeles. My family's roots stretch five generations back through Los Angeles history. It's in my blood. I'm a traveler at heart, but my home will always be California, and as you read last week, I often get nostalgic about Los Angeles.

This appreciation of Los Angeles is no secret. Admittedly, I get defensive of the city. Many of its detractors quickly glance at the film and television industry and dismiss this city as a vapid, shallow, image-obsessed mess of sprawl, but I find it one of the least superficial places I've lived. Los Angeles's beauty often lies many layers deep, visible in an unheralded neighborhood off one of the major traffic arteries, tasted in the melange of its countless subcultures' cusines, or heard in the crackle of hundreds of languages spoken throughout the city. Los Angeles is multi-centric, and beauty seeps between the megalopolis's many cores, often found in the transitional spaces between them firmly rooted in neither source nor destination.

Friends often ask what they should see and do in Los Angeles. This is always tough to answer because the city constantly evolves, as do my own tastes, and that doesn't take into account the unique preferences of the asker. Nevertheless, when a family of Austrian friends planned to stop in Los Angeles last summer, I compiled a list of suggestions based on their interests (seeing the beach, experiencing iconic architecture, and viewing landmarks). With a few changes and updates, I thought I'd share it with you.

Do not expect a complete guide to the city -- again, this guide was based on my experience and this family's interests -- but do expect a starting point. Nevertheless, as I did when I last posted a guide like this in 2009 I'm eager to hear in the comments what suggestions you'd add. Notably, this guide is heavily weighted toward Central L.A. and Downtown, where I've spent most of my time. The East Side (the real East side, not Silverlake or Echo Park), South Los Angeles and much of the West Side are under-represented. It's also worth noting that I wrote this for people traveling by car. However, much, if not all of this can be done via mass transit. I should know. Buses and trains were my preferred modality in Los Angeles and the subject of my graduate studies.

Anyhow, here's the guide.

Eating Los Angeles

Let's start with the food, because you could easily structure any tour of Los Angeles hopping from restaurant to taco joint to food truck. Meanwhile, the safest bet is Los Angeles Times food critic Jonathan Gold and his Essential 101. Trust me, just pick something from that list that fits your taste and budget. Gold is a fantastic food writer with a wide range of preferences. I've never been disappointed by anything I've tried from his suggestions, and there's a huge variety of price points from hole-in-the-wall to super-spendy. Be sure to read the fantastic 2009 New Yorker article about Gold before he moved from LA Weekly to the Los Angeles Times.

Downtown and Downtown-Adjacent

Definitely go Downtown and try to get inside building lobbies. If you have time, consider an LA Conservancy walking tour, which has expert, themed tours (and not just for Downtown). Looking at their list of current tours, I'd recommend the Historic Downtown or Downtown Renaissance tours, as well as the Angelino Heights one. Or look at the conservancy's list of self-guided tours. The 1960s architecture one could be a neat way to see town, and Venice Eclectic might be. Here's my own starter list of must-sees Downtown:

The Bradbury Building is a must. It's at 3rd and Broadway. You can go inside on the first floor and up to the first landing, but not higher because it's a private building. Still, that's enough to have you in awe and any trip to Downtown should include time to see it.

Across Broadway from the Bradbury, Grand Central Market is a large, open-air market that once was full of wonderful wholesale produce vendors, butchers and other grocers with a number of food vendors that made for a great, quick Downtown lunch. I unfortunately have not been for a few years. As I understand it, in recent years the food vendors have turned over as Downtown has gentrified and the place has lost some of its everyday vibe. But I'd still wager it's a pleasant place for a stroll, even if it has suffered the blanding hand of popularity..

The central branch of the Los Angeles Public Library is a dream, both for book lovers and architecture fans. It's a great library, but the real draw here is its main rotunda and old card catalog room, which is just stunning. The library also often has additional art exhibits near the Flower Street entrance.

Cole's is probably my favorite bar Downtown. It's one of two places that claims to have invented the French Dip sandwich (Cole's original French Dip is fantastic, but my favorite is the lamb with goat cheese). Other people will tell you that Philippe's has better french dips, but I just don't agree. The bar at Cole's also makes amazing pre-prohibition cocktails. On my 29th birthday, I orchestrated a Red Line bar crawl. I still remember the Whiskey Sour I had at Cole's that day (my first made with traditional frothed egg whites). Cole's bartenders are wonderful, and if you're into the celebrity spotting thing, its seems a good place to encounter famous faces in a non-gawker way. It's also a good place for general Los Angeles people-watching. There's also a speakeasy-ish bar (no password, just a hard-to-see door in the back of the main room) called The Varnish in back.

Hotel Figueroa at 9th and Figueroa features a quiet, often-overlooked bar with a patio by a pool great for a quiet hangout. It lacks all the clubbiness and douchiness of some other popular downtown bars. I'm not always thrilled by the cocktails there, but its relaxed atmosphere makes it a great place to stop for a bottle of beer or a simple mixed drink. To be honest, I'm out of touch with what's new in Downtown's bar scene, and there are others I know I liked and just can't recall right now, but you'll do fine.

The Redwood Bar & Grill on 2nd isn't just a great pirate-themed bar or the place where I happened to witness Barack Obama's historic election. It's also one of the favorite watering holes for Los Angeles Times reporters, who work just around the corner. Also, if you're interested in catching a symphony performance at the Frank Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall you won't have far to walk from here. Really, though, the best reason to go to the Redwood is the house made potato chips. Mmm. Chips.

I've heard great things about the renovation of the United Artists Theater next to the new Ace Hotel.

Little Tokyo should be self-explanatory. I don't have the best knowledge of restaurants and bars there, but as the heart of the largest Japanese population in North America, it's worth a visit and it's easy to access on foot or transit.

The recently-gentrified Arts District can be nice, but like many places, it can be frustrating to watch prices here skyrocket. Those familiar with Portland's own growing pains may be happy to know the Arts District doesn't have the same sterile, fake-seeming atmosphere as the Pearl District. Like adjacent Little Tokyo, I don't know the Arts District very well, but I did have a tremendous -- but spendy -- meal at Church and State, and wurstküche is tasty.

Across the 6th Street Viaduct from Downtown or a few stops on the Gold Line light rail is Boyle Heights, a heavily Latino neighborhood that used to be a major Jewish community and another of the many Los Angeles districts at the heart of gentrification controversies.

Echo Park (ish)

Echo Park, Silverlake, Los Feliz -- combined with a few smaller districts -- form the nucleus of hte most Portland-y, Brooklyn-y, Mission District-y, maybe hipster-but-still-cool, creative-but-almost-fully-gentrified parts of Los Angeles. The area is characterized by many hills, cafes, bars, restaurants and random shops, but it still features countless wonderful houses, hole-in-the-wall surprises and more. Here are a sampling of the places I love:

Located just south of Sunset and east of Echo Park Lake, Angelino Heights was Downtown Los Angeles's first suburb and is very much worth wandering around. Many attractive Victorian-era and otherwise notable homes remain in Angelino heights. Maybe don't make a special trip to go there, but if you're nearby it's worth a brief tour.

Echo Park Lake is lovely for a stroll or picnic, especially on weekend afternoons when the park is full of families having barbecues and vendors selling many kinds of food. It's an easy stroll from the heart of Echo Park and easy to get to from numerous bus lines, including the 704 Express. Plan to visit the lake yesterday when you combine a visit with a stop at The Echo Park Time Travel Mart, your one-stop-shop for time travel supplies and accessories. It's also a product of 826 LA, Dave Egger's literacy project. \

Dodger Stadium. If you're in town during the Dodgers baseball season, consider a game here. Opened in 1962, Dodger Stadium is now the third-oldest stadium in the Major Leagues. There really isn't a bad seat in the house; the reserve or top-deck levels are fairly inexpensive, for example, and they even offer the added benefit of gorgeous views of the San Gabriel Mountains. If you go to a game, the best place to get a pre- or post-game drink is the Shortstop on Sunset Blvd. Fans usually pack the bar before games, and there's often even a tamale vendor there who will bag up cheese or chicken tamales for you to bring to the game. You can then walk 15 minutes up hill from the Shortstop to the stadium. By the way, don't drive to Dodger stadium, where parking is expensive and takes forever. Instead, you can take transit to Union Station (oh, and I haven't even mentioned what a beautiful place that is) and catch the free Dodger Stadium Express, which even has a Dodger-logo-marked lane exclusive to the shuttle on game days. Bus riders can also take the line 2, 4, or 704 buses to Elysian Park or Douglas, especially if they want to stop at the Shortstop.

Griffith Park Vicinity

You might combine a visit here with Los Feliz, Silverlake, Echo Park or some combination thereof. These neighborhoods are close to one another, but it can get exhausting to try to go to all of them at once.

Los Angeles River Center & Gardens. This is a really pleasant little place to learn more about the LA River, its ecology and recent efforts to restore the waterway. This facility is an old spanish-style complex right by the river with a nice courtyard and a variety of interpretive displays and views of the river.

You've likely seen the view from Griffith Park and Observatory in the movies, but do make a plan to see it for yourself. The park features wonderful hiking trails that show off Southern California's natural landscape and fantastic views of the city simultaneously, and it's all located right in the heart of Los Angeles. Meanwhile, the observatory itself offers tremendous views itself. Admission and parking is free, as are a number of educational events and star parties, while the planetarium has a reasonable fee for its shows. Even though parking is free at the observatory, it can be tight; on the weekends, consider taking the Los Angeles Department of Transportation's DASH shuttle up to the observatory.

The Greek - This outdoor concert venue is one of the best places to see a show in Los Angeles. If there's an act coming that you want to see, I highly recommend doing so.

Silverlake

The Neutra VDL House at 2300 Silverlake Blvd. is open for tours highlighting Neutra's modernist architecture. It's one of many great architectural tours one can take in Los Angeles.

Probably not too shockingly, the Silverlake Reservoir is the man-made body of water from which this neighborhood derives its name. The reservoir is always a lovely place for a walk and it offers a great opportunity for people (and dog) watching!

Silverlake, Echo Park and other nearby neighborhoods are home to countless semi-secret staircases that offer a unique way to get some exercise and explore these neighborhoods. While the Music Box Steps made famous by Laurel & Hardy are probably the most notable, many of the other staircases offer even more surprising and interesting views. Couple them with a walk around the reservoir, then get a meal on Hyperion, Silver Lake Blvd. or Glendale Blvd. (I like Gingergrass). Alas, you can't follow up with a show at the Spaceland anymore, but now apparently you can go to the Satellite instead.

Need a coffee? LA Mill can verge on coffee snobbery, but it is nevertheless quite tasty with a huge menu. And though it's a scene, it's not the hipper-than-thou seen I seem to stumble into at nearby Intelligentsia.

Oh, The Red Lion, the memories I have of you. Coming up with excuses not to sing karaoke in that tiny room upstairs, squeezing into a corner for trivia, making out in your parking lot the first time I ever went there. This German bar has a huge, busy upstairs patio, a cozy alcove for the aforesaid karaoke and trivia, and a chill piano lounge downstairs. The beer selection is wonderful. Though the weekend crowd at the Red Lion can get annoying, this is still one of my favorite watering holes in this part of town.

Los Feliz/East Hollywood

The Barnsdall Art Park is home to the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Hollyhock House, which recently reopened after restoration. Located on a large bluff near Sunset and Vermont, the park provides 360 degree views of the city, while the Hollyhock House is as cool as you'd imagine an FLW design can be. But the most fun way to see it is to go one of the park's Friday evening wine tastings, which combine great wine, lovely views, and beautiful people. You can either bring a picnic or order from one of the food trucks that come up for the event.

Upper Vermont Ave in Los Feliz features a host of small clothing shops and eateries, a movie theater, and the independent Skylight Books, one of the best book stores in Los Angeles. It's also where you'll find the Dresden Room and its five-nights-a-week jazz duo Marty and Elayne. While you're in the neighborhood, be sure to go down Vermont around around to Hollywood Blvd. for a stop at Wacko Soap Plant. It's a huge store packed with graphic novels, coffee table and photography books, nick nacks and a huge selection of the kind of ephemera that your average Spencers Gifts seems to be shooting for, but constantly misses. Nearby Hillhurst Ave. offers a more low-key, local taste of Los Feliz. Don't forget that all of this is an easy walk from the Sunset/Vermont Red Line Station.

Located at Franklin at Tamarind in the tiny but cute stretch known as Franklin Village, the Bourgeois Pig was one of my favorite places to work on my Master's project. Next door to the Upright Citizens Brigade, the Bourgeois pig's real charm isn't its coffee or pool table, it's its back room, which features a fanciful forest scene, or it did when I was last there. It's a great place to get some writing done and yet another good place for people watching.

Upright Citizens Brigade: I haven't been, but the actors who perform in its improv comedy troupe are everywhere and hilarious. I'd trust a show here to be great.

You like ice cream, don't you? Then get yourself to Scoops at Melrose and Heliotrope post-haste! There are also scoops locations in Palms and Highland Park, but this is where they got their start. What are you waiting for? Have some ice cream now! These guys were making crazy and amazing ice cream flavors before Salt and Straw was even a a food cart. It is unbelievable. Transit-bound? Take the Subway to Santa Monica/Vermont or one of many bus lines traveling on Vermont, Santa Monica, or Melrose.

Mid City/Wilshire Center/Koreatown/Miracle Mile/La Brea/Fairfax/Hollywood

Hancock Park - Big houses on tree-lined streets that aren't quite as gaudy as Beverly Hills. Kinda fun to see if you're going somewhere else.

Larchmont Village - a little yuppified, but some pleasant places to stop for a walk.

Hollywood Forever Cemetery - Santa Monica Blvd behind the Paramount Studies. In the summer they have movie showings and concerts. It's surprisingly not creepy and it's fun.

The weirdest Kentucky Fried Chicken you've ever seen. No, really, it must be seen. Not eaten at, and I'd only stop if you're in the vicinity, but it must be seen.

Korean BBQ. Check Jonathan Gold's rec's for the best places, but you can rarely go wrong. Also find a cheap place for bibimbap (generally less expensive than the BBQ places, which can get spicy easily).

The Los Angeles County Museum of Contemporary Art. It's a truly great museum with fantastic exhibits, and I think they have a monthly free day.

La Brea Tar Pits. The museum itself might not be worth admission, but there are big tar pits right outside one can walk around. This is right next door to LACMA.

Largo - probably the best place in LA to see comedy. Check out the list of regulars (Tig Notaro, Sarah Silverman, etc.) and you'll see why I say that: . Any show there would be amazing.

Canter's - an excellent 24-hour Jewish deli in the Fairfax district. Really an awesome, hang-out place. The Kibbutz Room next door is a bar. Go here any time, very possibly see someone famous, definitely have a great traditional Jewish deli meal.

Farmer's Market - This is a different big open-air market that has existed for ages. It's more touristy than Grand Central and it's next to an obnoxious mall, but I still enjoy it. When my mother was a little girl, my great-grandmother used to take her to the Farmer's Market, and from all reports it hasn't changed much.

Little Ethiopia just south of Wilshire on Fairfax should be self-explanatory. And it certainly is tasty.

Hollywood and Highland is like, but not quite as bad, as Times Square. Some people enjoy see the stars of the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the Chinese Theater, and the costumed superheroes, but this place is so, so touristy and tacky. Proceed with caution. There ARE two subway stops in Hollywood for a quick jaunt from Downtown.

The Hollywood Bowl, on the other hand, is worth every bit of hype it receives. This is a primo, amazing outdoor music venue. The LA Philharmonic plays here all summer, and there are often great popular acts playing with orchestras. I can't begin to describe how beautiful a night here is, but it is certainly pricey and a bit of a pain to get to (but not a bad walk from the Red Line at Hollywood and Highland).

Trains and Automobiles

Despite my love of all things mass and active transportation, for short visits, I have to admit that it is easy to get around with a car. And access to a car gives you the chance to drive Mulholland Drive. It's certainly hyped, but worth it. There are beautiful views everywhere, you can see the whole expanse of the city, and there are numerous pullouts from which you can take in the view or do short walks.

However, one can easily see Los Angeles without a car. Take the Metro Los Angeles Red Line subway between Downtown (from Union Station, itself a gorgeous 1939 example of the great American train station) and North Hollywood, where you can transfer to the Orange Line, a bus rapid transit system operating in an old rail right-of-way that gives you access to the San Fernando Valley, which put the "valley" in "valley girl." Along the Red Line, you can stop in multiple parts of Downtown, MacArthur Park/Westlake, Koreatown, the trendy Los Feliz neighborhood, Thai Town/Little Armenia and Hollywood. One can also take a variety of light rail lines, all but one of which have hubs Downtown. The Gold Line travels to Pasadena, which features a cute downtown, great museums and a number of Craftsman homes; it also passes through Chinatown, the rapidly gentrifying Highland Park and a few other locales in one direction, while the other takes riders through Little Tokyo and on to East L.A.

The new Expo Line goes to USC and nearby Exposition Park, home to many fantastic museums. Most notable among those are the California Science Center (which houses the Space Shuttle Endeavour and the Natural History Museum in particular, as well as a nice rose garden. The Expo Line then continues through South Los Angeles to Culver City, a pleasant little town that, among other features, claims the ABSOLUTE MUST SEE stop that is the Museum of Jurassic Technology. I won't say more about that museum because it's really too insanely weird and it's worth every bit of surprise you'll have there. Next year, the Expo Line will be able to take you all the way to Santa Monica.

The Blue Line, meanwhile, will take you through South Los Angeles to Long Beach, while the Green Line, the only line that doesn't connect to Downtown, travels between the Beach Cities and El Segundo.

Beaches

Speaking of beaches. Most of the beaches right by the actual city of Los Angeles are rather crowded, but may be worth a one-time visit for the experience. Still, the adjacent community of Hermosa Beach has a very nice beachside walkway called The Strand, with the ocean on one side and expensive houses on the other. Manhattan Beach offers a similar promenade. Nearby Redondo Beach is a little shabbier, but not much. Personally, I find each of these communities less interesting than the rest of Los Angeles, but they still have certain lazy charms. The nearby Palos Verdes Peninsula may merit a drive around for expansive views of the ocean, but it's otherwise quite quiet. However, it's worth mentioning that the peninsula holds the remaining wreckage of the ship once known as the SS Melville Jacoby, which was named after the subject of my upcoming book. Later renamed the Dominator, the Jacoby shipwrecked on the north side of the peninsula in 1962. Though its pieces are slowly vanishing, It's a pretty impressive sight to see.

Back in the city proper, Venice Beach received its name from a network of lazy canals that weave behind multi-million-dollar homes. This community also features a trendy and expensive shopping street called Abbot Kinney. Despite its skyrocketing prices, something could be said for a stroll on Abbot Kinney, though it's not without many often valid critiques. On summertime Fridays, the street plays host to many of Los Angeles's iconic food trucks, but as bustling as the district becomes on these nights it also gets mobbed with diners and revelers. But the feature for which Venice Beach is most known is its boardwalk, which is as funky as you've probably heard and worth seeing once. It's certainly touristy, but not in a completely off-putting way. Here you'll find a crazy mix of peddlers, street performers, scam artists, weirdos, bodybuilders, tourists, and any other character you can imagine.

Nearby Santa Monica has great views and a touristy pier. The open-air 3rd Street Promenade is lined mostly by chain stores, but for a shopping street it is nicely-designed. Other districts in the town are far more enjoyable, such as Ocean Beach and Main Street. The beach in Santa Monica certainly has room for lounging, and the city is a nice enough town, but even though I've been through a gazillion times I don't have much to say about it. What I do know is this, the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy just north of town is unbelievably gorgeous. There you can find miles and miles of coastal mountains and sagebrush hills to hike, some with ocean views.

Further up Pacific Coast Highway is fabled Malibu, a long stretch of highway with expensive but precariously located homes. It's probably not worth a special visit, but if you're driving north you might consider taking PCH instead of going inland on the 101 or the 5. If you're looking for a great beach, many of the hidden coves and beaches in Malibu and beyond are the region's best. Ones I've heard of or know are good include El Matador and Leo Carrillo, but these are far from the only beaches worth trying. Look for signs that say "beach access," and don't get too discouraged by the gigantic homes. A huge fight has been between waged homeowners and the public about beach access. There's plenty of reading to be done about the conflict, but know that it's your right to visit many of these, so don't let the no-trespassing signs fool you.

Miscellaneous

The Huntington Gardens features a beautiful library and an even more beautiful garden in Pasadena, which is worth a visit itself.

I think this blog post put together by Elizabeth Laime of the wonderful (and lamentably just-ended) podcast Totally Laime has a lot of great ideas. While you're checking that post out out, give a listen to old episodes of Totally Laime or subscribe to their other shows: Totally Married, Totally Mommy and Totally Beverages and Sometimes Hot Sauce (which is about exactly what it sounds like, and is, well, totally rad).

KCRW - great music every morning, night, and weekend, and a wonderful source for current events during the day (notably with its To the Point and Which Way L.A. shows). It's also a good place to listen for local events/happenings/etc. Find it on the air at 89.9 FM.

Where KCRW is the place to turn for new music in the Los Angeles area, KPCC at 89.3/Southern California Public Radio has fairly robust coverage of Los Angeles and Southern California on the radio and online. Even commercial radio in Los Angeles claims quality journalism, from KNX's seemingly ubiquitous Claudia Peschiutta (and the station's earworm of a traffic update alert) to Wendy Carillo's Knowledge is Power show on Power 106.5.

While it has seen troubles at the highest levels of management, the Los Angeles Times remains a tremendous source of journalism, and many of its individual reporters and columnists are among the best in the business.

Nathan Masters's L.A. as Subject blog is a consistently educational and entertaining read about the history of Los Angeles.

The Militant Angeleno, an L.A. native, may or may not provide far better tours of the hidden corners of Los Angeles than I'm attempting here.

Three times a year, major Los Angeles streets are closed for CicLAvia, which gives bicycle riders, pedestrians, skaters and such access to these streets and a fun opportunity to see Los Angeles from a perspective usually only afforded to cars. It is truly a blast to participate in.

I've just realized I've forgotten the Getty Center. Many people are more impressed by this museum's grounds than its collection. For good reasons. This free museum sports some of the best views of Los Angeles.

There are many, many, many other places I've failed to mention or describe in any worthwhile detail. Likewise, I have neglected areas as varied as Leimart Park, Westwood, the San Fernando Valley, West Hollywood, Atwater Village, Marina Del Rey, the Port of Los Angeles, Crenshaw, Westlake and Laurel Canyon , but I hope this can be a start for your experience of Los Angeles and for my own thoughts about it. Again, I'm eager for your suggestions.

Los Angeles Remembered and Imagined

Some people who visit Los Angeles scan the city for stars, but I gaze beyond the stars to see the city.

This evening with dinner, as I often do with meals, I watched an episode of the television show Parks and Recreation. As this particular episode's resolution neared, Leslie Knope and her merry band of bureaucrats gathered outside a decrepit warehouse in a run-down corner of Pawnee, the imagined small "Indiana" town where the show is set and which always seems to reveal another as-yet uncovered neighborhood.

Taking full advantage of dramatic license, the show's creators take few if any efforts to disguise the show's Los Angeles Basin filming locations as the Midwest. Anyone who has seen the show and has also visited Pasadena instantly recognizes that Los Angeles neighbor's city hall playing Pawnee's on television. Tonight, I recognized Beachview Terrace, the "armpit of Pawnee," as Clarence Street, one of the roads in the district of wholesale food warehouses on the East Bank of the Los Angeles River, beneath Boyle Heights.

It wasn't just that I recognized the pylons of the Six Street Viaduct in the shot's background from other Hollywood productions. Instead, in August 2013, I'd run down that very street on the 12th or 13th mile of a training run for the Portland Marathon. One of the best runs I've ever taken, it took me from my friends' house in Highland Park, down the Arroyo Seco, along the edge of Montecito Heights, around Lincoln Heights, through the USC Keck School of Medicine, past the 10, 5 and 101 freeways, into Boyle Heights, down into the warehouse district, across the river into the Arts District and up to its finale in Little Tokyo (from whence I returned to Highland Park by Los Angeles's Gold Line. Yes, Virginia, there is mass transit in Los Angeles).

That Sunday was glorious. The weather was perfect (Despite unseasonably cool and foggy weather during most of my visit that August), the streets were peaceful and quiet, and there was a festival with traditional drumming -- and Japanese food -- when I stopped in Little Tokyo. That afternoon, my friend and I returned Downtown for a lazy afternoon gazing at the San Gabriel Mountains and watching baseball from the glorious upper infield seats of Dodger Stadium (note: There really isn't a bad seat in the house).

Why I mention all this now is that the sight of that alley so quickly brought this memory back to me. One of my favorite past-times when I visit Los Angeles is realizing a particular building or corner or vista is one I recognize from film or television, and when I'm elsewhere, a particular shot in a movie or T.V. show will evoke some memory from childhood trips to see family, meandering dates during grad school, trips with partners, or adventures across town with friends. Some people who visit Los Angeles scan the city for stars, but I gaze beyond the stars to see the city.

Clearly, the confluence of my personal history with the film industry's is responsible for much of this. Many people are familiar with Los Angeles because it has been so many things to so many people. While I explore this phenomena from an informal perspective intertwined with memory, the city's starring role in our imagination was deftly dissected in the 2003 documentary "Los Angeles Plays Itself." Recently remastered and released to the wide public for the first time ever, this movie masterfully chronicles the city and the film industry with a precision and a breadth of knowledge that I cannot approach. Yes, I am often a cheerleader for this city, but even if you don't care for Los Angeles, perhaps particularly if you don't, do give this movie a try. Director Thom Andersen composed a fantastic work. At the very least, it will inspire you to watch any number of films you may have missed, but I suspect it will also provide a new lens with which you might view Los Angeles and the stories it's used to tell.

I'm sure the sense of familiarity I felt watching Parks and Rec tonight doesn't only happen in L.A. Here in Portland people are perhaps a little annoyed, but also thrilled by seeing our city through the nation's lens for the past half-decade. Many people, no doubt, often see New York and remember great nights of their youth, or watch the West Wing or House of Cards and wonder why that summer they interned on Capitol Hill wasn't as fun. Etc.

Whether depicted on the screen, or not, what are the fragments and images that linger of the towns you're from, the towns where you are, or the towns where you've been? Which are the places woven deep into your heart? What about those places far away from towns, those places perhaps only you know? Where have you been that stirs you, and to which you can be brought back in just an instant? What are the triggers that bring you back there? What are the moments you remember from these places? Let me know in the comments.

Stay tuned tomorrow. I'll be sharing my updated personal guide to Los Angeles!

Sights seen while not writing

As I noted last week, I don't just write: [shashin type="photo" id="279,867,863,865,976,963,941,848" size="medium" columns="2" order="user" position="center"]

In Transit

More formally known as the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Agency, Metro offers more than buses and trains. It exudes personality, a personality interwoven with this vast community. Many claim Los Angeles has no public transit, but I know otherwise, and this afternoon's ride only cements my opinion. A bus driver stopping randomly alongside the road might not be the model of efficiency, but he embodies the charm of transit in Los Angeles. I've heard of bus drivers who croon Rat Pack hits as they carry passengers to and from their homes; I've watched flirtation blossom to affection on the platforms of the Green Line. I've watched drunken partiers stumble down bus aisles then politely strike conversation with late night commuters. I've even seen gangbangers politely offer their seats to elderly and disabled passengers.

In Spring, 2009, I wrote this commentary about my personal experiences with transit in Los Angeles. An assignment for a class, it was something of a companion to the reporting I'd done for my master's project, the work that became “R We There Yet.”

In Transit

“Have you seen my boy Wayne?” the driver, smiling, calls out to a man on the sidewalk as he pulls over the #26 Short Line along Avalon Boulevard in the middle of South Central Los Angeles. It's a Saturday afternoon in early February. This isn't an official stop, and it's not the first time the driver has pulled over to say hi to a pedestrian he recognizes.

I'm sitting a few rows behind the driver, and suddenly it hits me: I realize that I'm falling head over heels for Metro, the largest transit operator in Los Angeles County.

More formally known as the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Agency, Metro offers more than buses and trains. It exudes personality, a personality interwoven with this vast community. Many claim Los Angeles has no public transit, but I know otherwise, and this afternoon's ride only cements my opinion. A bus driver stopping randomly alongside the road might not be the model of efficiency, but he embodies the charm of transit in Los Angeles. I've heard of bus drivers who croon Rat Pack hits as they carry passengers to and from their homes; I've watched flirtation blossom to affection on the platforms of the Green Line. I've watched drunken partiers stumble down bus aisles then politely strike conversation with late night commuters. I've even seen gangbangers politely offer their seats to elderly and disabled passengers.

Occasionally, I'll overhear someone declare “I'd take public transit in Los Angeles if it went near me” and I'm baffled. Metro operates more than 2,000 buses on 200 routes during its peak hours, as well as two subways, three above-ground light rail lines, and a “busway”—an old train right of way in the San Fernando Valley that has been transformed into a roadway devoted to fast-moving, high-capacity buses. My own exploration suggests just how many places in Los Angeles the system reaches.

I can take the bus to the beach or down Sunset Strip. I can visit friends in the Miracle Mile and family in Pacific Palisades. I can do my grocery shopping at the Hollywood Farmer's Market or browse the boutiques on Melrose and Third Street. I can eat my way across the city, grabbing noodles in the Okinawan neighborhoods of Gardena or Korean barbecue from a hole-in-the-wall on Olympic Boulevard. I can even take the bus to the happiest place on Earth. That's right, for less than two bucks I can catch a ride from Downtown L.A. to Disneyland.

Every ride gets me to my destination, but there's more. Every ride is an adventure. Every ride leaves me with a story to tell.

When I drive, I have to find my way around wherever it is I am. Driving requires me to focus on the road, not my surroundings. Riding the bus let's me leave the details to the bus driver. I am free to enjoy the scenery, eavesdrop on fellow passengers, read books, listen to friends, nap, study, or write. I can come and go when I please, without searching for parking or worrying about what condition I'll find my car when I get back. If I over-imbibe after a night out I can get home without worrying about risking anyone's life.

Recently, I had an experience that helped me put this in perspective. A few weeks ago I decided to take my car on an errand, ironically enough at Union Station, Metro's hub and headquarters (where I went in search of Metro souvenirs for a friend). Normally to get from my house to Union Station, I pay $1.25 for a Metro ticket or buy a $5 day pass and hop on the Red Line subway at Wilshire and Vermont. At Union Station, I can transfer to other rail lines, get on a bus headed any direction, or even pay $4 to catch a shuttle that will take me straight to my terminal at Los Angeles International Airport.

But this day, I drove, thinking I needed my car for flexibility to get to the station then off to USC in time for a yoga class. I negotiated tractor trailers and impatient commuters on Highway 101, merged onto Alameda St. and pulled into the station's parking lot. At Metro's gift shop I spent some time browsing for my friend's present and pondered buying a transit pass, then got back in my car. I paid six dollars for parking and headed to the 110 to make my way to USC. There, I fed two more dollars to a meter on Jefferson for two hours more of parking. After class, I drove through start and stop traffic up a packed Vermont Avenue. Relaxed when I left class, I felt my loosened muscles tense as I inched through the two miles home.

According to estimates from AAA, the day's driving probably cost me more than four dollars simply for fuel and wear and tear on my car. Add in parking and I spent more than $12 on a couple quick errands. Had I taken the bus, I could have completed the same trips for less than half that, and let someone else do the driving.

Seems like a great deal. So what's the catch?

For some people it's the stigma.

This morning I rode the #204 — which travels 13 miles through the center of Los Angeles along Vermont Avenue between Los Feliz to the North and the community of Athens in the South, near the 105 freeway. I sat in the rear of the bus facing one set of windows with my back to another set. I watched the passing streetscape, the morning's first bustle of commerce and the people running to catch the bus down sidewalks spotted with gum. But my view was clouded by rain spots caked on the windows' exterior, and the jagged contours of graffiti etched into the thick plexiglass. Scanning the bus's interior, I saw tags all over, from the backs of seats to the curved gray ceilings of the vehicle.

But despite the graffiti, the buses are clean and well lit.

Some people are simply confused by Metro. They avoid it because the transit network seems so foreign.

Caged in our automobiles, learning a transit system can be like learning a new language. At first, the squiggles and lines criss-crossing route maps and the figures filling bus schedules can look like hieroglyphics, but given time and a little bit of trust they quickly begin to make sense, and soon, the serenity of understanding this secret code sets in.

“The city does not have a reputation for really having any public transportation,” Erin Steva, a spokeswoman for the California Public Interest Research Group, says. “Clearly it does and it does work for many different people, but it does need to improve.”

Steva rides her bike and takes the #603 and #201 buses and the Purple Line Subway to her office near the intersection of Wilshire and Western Avenues.

So how can Angelenos make the bus work for them? They don't have to do anything more than stretch their legs, leave their cars parked in their driveway, walk down the street and board one of hundreds of bus routes crisscrossing the city and the surrounding county. It's not a perfect network, but it's a delightfully quirky system far removed from the fist-clenching aggravation of traffic jams and parking woes. L.A.'s buses, like its bike trails and its rail and subway networks, need vast improvements and expansion, but the billions of dollars it will cost to invest in the system's future are easier to accept for those who’ve spent any time using and even enjoying it.

Last fall, voters were so fed up with traffic that they voted to tax themselves to pay to improve transit in Los Angeles County. In the midst of an economic crisis they passed Measure R, which guarantees $40 billion in sales tax revenue to pay for transit infrastructure improvements over the next 30 years. Even though $8 billion of that might go toward improving Metro's bus network, it might not be enough. Measure R pays for capital improvements, for new things — things like new railways, bus only lanes, and timed traffic signals. It doesn't pay for people. It won't pay for bus drivers' salaries or maintenance crews.

So Metro's day to day operations remain at risk. To cover gaps, Metro's board finds itself choosing between slashing routes and raising fares. The latter isn't politically expedient, but the former could dramatically impact tens of thousands of people's lives. Metro’s fares are some of the lowest in the country; yet officials know that about 75 percent of the system's bus riders make less than $12,000 each year. While taking the bus is an attractive option to me, those riders don't get to make a choice. They need the bus and the train to get to and from work, to take their kids to school, to get to the doctor's office, to visit their friends and to run errands. If service is cut, their very lives will be at risk.

If more people who CAN choose realized how easy, how comfortable, and yes, how charming it is to ride a bus, perhaps we'd put more pressure on politicians to avoid making such lose-lose decisions, to avoid starving a lifeline so essential to our city. We can ride the bus, learn how much freedom and adventure it can bring to our lives and demand transit as a right.

Thousands of years ago, the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu said “The journey of a thousand miles begins beneath one's feet” The lesson isn't any less true when it comes to journeys of a few miles from the movie lots of Hollywood to the classrooms of UCLA, or between the spectacular views from Griffith Park to the crashing waves of Manhattan Beach. From the broad boulevards of the San Fernando valley to the Art Deco towers of Downtown's historic core, the journey toward a sustainable future for Los Angeles begins with small steps—beginning with an appreciation for what exists today.

R We There Yet? Re-evaluating Los Angeles's Transit Future

It's becoming clear that the age of the automobile is coming to an end, or, at the very least, changing. Los Angeles, like other cities, loses billions of dollars each year just because of people stuck on the region's tangled roadways. Scholars, politicians, activists and numerous overlapping government agencies each offer often-competing solutions for how to get the region moving. All the while, the solution might begin not with expensive upheavals and construction of vast new transit networks, but instead with better cooperation, education and mobilization of the surprisingly robust transit network that already exists in the metropolis.

Looking ahead on the gold line. (Photo by Bill Lascher)

"Out Of Service,” The Driver Tells Me As I Step On The #4 In Downtown Los Angeles.

It is nearly 3 a.m. and Broadway's indoor swap meets, electronic stores and jewelry shops sit darkened behind me. Shadowed by the marquee of an ancient movie house my face betrays concern, perhaps even desperation. I've waited to catch a bus for nearly an hour alongside the vacant thoroughfare after staying out with a friend and missing the night's last Red Line subway. It's cold. The bus already carries about a dozen riders, so I don't understand why the driver seems to be telling me I can't board. Not wanting to linger on the street much longer, I pause on the bus's steps.

“Out of service,” the driver repeats. I step back down to the sidewalk. She laughs, smiles, and rolls her eyes.

“I didn't say you can't get on,” she teases, as if she's going to finish the sentence with “rookie.”

It's the farebox that's “Out of Service.” I jump back onto the bus and find a seat along the center of the bus, where its two sections connect like an accordion. None of the other riders pay me any heed. Each haggard face exudes fatigue. Two women, both dressed in identical white pants and white sweatshirts, sleep leaning against one another. Perhaps a mother and daughter, perhaps middle-aged sisters, one rests her shoulder on the other, who is slumped against a rattling window. Their long brown hair tangles together.

It's becoming clear that the age of the automobile is coming to an end, or, at the very least, changing. Los Angeles, like other cities, loses billions of dollars each year just because of people stuck on the region's tangled roadways. Scholars, politicians, activists and numerous overlapping government agencies each offer often-competing solutions for how to get the region moving. All the while, the solution might begin not with expensive upheavals and construction of vast new transit networks, but instead with better cooperation, education and mobilization of the surprisingly robust transit network that already exists in the metropolis.

What's certain: voters in Los Angeles County are fed up with traffic. Confounding expectations, they accomplished an extraordinary feat in November, 2008 and gambled that an investment in the region's transportation network would pay lasting dividends. Despite an economic downturn, more than two-thirds of them chose to tax themselves to pay for Measure R, a $40 billion expansion of the region's transit system. Since July 1, the county has collected a half-cent sales tax to pay for new rail lines, expanded bus routes, and improvements to existing infrastructure. But a debilitating state budget battle earlier this year put transit in a precarious position across California, including Los Angeles, whose position among the world's great cities could be at risk.

“We're going to fight tooth and nail for every penny from the state,” Richard Katz said in January. Katz sits on the governing board of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Metro, by far the largest transit agency in the region. A former state assemblyman, Katz was appointed to the board by Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and was a key architect of Measure R. “I think we make a mistake if we don't recognize that the voters made a clear choice in November. They said transportation is the number one issue in the county. We're going to give you the resources to fix it and we expect you to fix it. They don't expect us to be whining about losing $200 million a year.”

As the #4 bus carries me past Union Station it turns westward on Cesar Chavez Avenue. I notice how the prerecorded voice announcing each stop perfectly pronounces the deceased farm labor organizer's name. A few blocks away, after Cesar Chavez Avenue becomes Sunset Boulevard, the recording stumbles over a cross-street's name, uttering Micheltorena like a Gringo. The sleeping sisters are oblivious to their surroundings, until a few blocks later, when the bus stops at Sunset and Alvarado. Two middle-aged men drunkenly babble to one another as they board. They stumble in search of a seat, startling the women.

The bus turns down Santa Monica Boulevard. I disembark at Vermont Avenue, where I can connect with the #204, a North-South line with a stop a block from my apartment. A light drizzle falls as I wait in the dark along Vermont. A dozen or so men line the curb, peering north up the street. A few step into the road. If only they could spy the bus, it seems, they could will it to carry us out of this uneasy wait sooner. It's about 3:30 a.m. The only passing cars are taxis hoping to pick up a few desperate fares. The drunks who earlier boarded the #4 stand next to me, talking about the relative morality of stealing bicycles versus cars and beds. They reminisce on times they've had to pull guns, what it felt like with the finger on the trigger and the experience of staring down the barrel of a friend's firearm. Illustrating one such experience one of the men mimes a pistol with his fingers outstretched.

“Those days are gone,” he says.

Profit and loss

Travelers pass an information kiosk near the entrance of Los Angeles’s Union Station. (Photo by Bill Lascher)

Three months earlier the stock market was crumbling. News of layoffs increased in frequency. Home foreclosures ticked up. A historic election took place. But it wasn't Barack Obama who delivered a nail-biter in Los Angeles County. It was Measure R.

It took a month for elections officials to certify the close vote. The requirements were stricter than ballot measures that only need a simple majority to pass, because state law requires new taxes to pass by two-thirds majorities. Measure R barely cleared that higher bar, winning just a bit more than 67 percent of the electorate.

Most of the $40 billion the measure is expected to generate over the next 30 years will go to Metro, which operates about 200 bus routes in the county, the Red/Purple line subway, the Orange Line rapid busway, and three light rail lines (See Transportation Terminology). Each of L.A. County's 88 embedded municipalities will also get a share for transportation projects. Metro officials are currently hammering out exactly how their share will be spent and when, but it's expected to pay for new light rail lines, a long-anticipated Subway to the Sea under Wilshire Boulevard, and other projects.

Preliminary estimates from the Federal Transportation Administration suggest the massive economic stimulus package passed by the U.S. Congress and signed by President Barack Obama in February could pay for about $190 million of transit improvements throughout Los Angeles County.

Yet gains from the stimulus and Measure R may be thwarted by news at the state level. Only days after the stimulus package passed, lawmakers in California ended long-stalled budget negotiations in the state. As many transportation advocates and agency officials feared, in the weeks and months leading up to the deal, millions of dollars in assistance to transit agencies throughout the state were slashed from the final budget.

For hundreds of thousands who rely on the region's buses (about 75 percent of Metro's bus riders make $12,000 or less annually), any cuts sting.

“They're the reason the agency exists,” says Katz. He says government should focus more on transit, especially in a city as sprawling as Los Angeles. “We have people in L.A. who, were it not for our system, could not get to work, could not get to school, could not pick up their kids, could not get to health care. Public transit is an integral part of the fabric of this city.”

Los Angeles' love affair with the automobile is a myth. It's not the nation's most car dependent city, nor does it have the worst transit network in the U.S. (See “Does L.A. Really Love its Cars?”). But while it might be a myth that Los Angeles residents own more cars than inhabitants of other cities, or that the city has no public transit, the metropolis faces harsh realities. Angelenos may not love cars, but they're stuck in them. Many studies show the metropolis' traffic is the worst in the country, a situation explored by an Oct. 2008 RAND Corp. study called Moving Los Angeles: Short-Term Policy Options for Improving Transportation. Traffic costs Los Angeles dearly. Each year, the area's economy loses more than $9 billion simply due to the 490 million hours drivers collectively spend sitting still in their cars. To put it another way, each driver in the region spends three days stuck in traffic annually. During those three days, individual drivers burn 57 gallons of gasoline without going anywhere.

“Reducing congestion should help to improve quality of life, enhance economic competitiveness, reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, improve air quality, and improve mobility for drivers and transit patrons alike,” the report read.

So why can't Angelenos get anywhere if they don't own many cars and there's such an incentive to cut down on traffic? The answer can be found by dispelling one more myth, that L.A. is a mecca of urban sprawl.

Entering the Mariachi Plaza Station of the Metro Gold Line on Nov. 15, 2009. (Photo by Bill Lascher).

In fact, Los Angeles's suburbs are actually the country's most densely populated. While more people might be packed into the urban cores of Manhattan and Chicago than Downtown Los Angeles, more people per square mile live in Los Angeles' surrounding suburbs than anywhere in the country. Normally, density helps shorten the lengths of drivers' commutes, but that's not true in L.A., where more drivers compete for the same road space. There is still congestion in other dense cities, but they also have direct transit alternatives. In Los Angeles, that's not always the case, because the area doesn't just have one central urban core or Downtown. It is “polycentric.”

Los Angeles isn't a sprawl of low density suburban communities. Instead, the city and its surrounding metropolitan area have multiple “Downtowns,” including Century City, Santa Monica, Culver City, Pasadena and Glendale, to name just a few. This polycentricity makes public transit more logistically difficult. Commuters don't just move between a suburban periphery and a dense core – they move in multiple directions at all times of the day. So many trips in so many directions across a polycentric city require a more complex transit network.

Thus, a metropolis like Los Angeles, with a complex mesh of roadways already in place between its urban centers, can't just build its way out of congestion with new rail lines. RAND's study recommends 13 traffic-management solutions policymakers could adopt in the short-term. The ideas include capitalizing on the robust bus network that already exists in the Los Angeles area, as well as other ideas, such as parking meters that charge different rates depending on the time of day and location, incentives for ride sharing, and special toll lanes for high-occupancy vehicles.

All these goals, the report says, would serve to help manage demand for Los Angeles' limited road space during peak hours. Such demand management is criticized because its impacts tend to wear off over time, but, say the RAND report's authors, it might work if regional planners simultaneously develop strategies to put a price on the amount of use drivers get from the region's roadways. Meanwhile, the report suggests, the pain lower-income commuters might feel from higher driving costs would be alleviated if convenient and reliable public transit were protected and improved.

New rail lines and realignment of zoning and planning rules to improve land use may be long-term solutions, but the team studied only projects that were likely to measurably decrease the number of cars on the road. ”The region could implement such projects quickly and they could be addressed without needing to engage numerous stakeholders simultaneously. Problems like diesel truck traffic carrying cargo from L.A. and Long Beach's busy ports — a major contributor to both the region's traffic congestion and air pollution — weren't within the scope of the study. Instead, RAND looked at solutions that could be implemented quickly, while policymakers debate extensive, long-term changes, such as those Measure R might allow or the complexities of cargo truck traffic. But some of these policymakers say change is overdue.

“L.A. is way behind,” Katz says.

I meet Katz on a rainy January morning before a Metro board meeting. When I first arrive at Metro's Downtown headquarters I can't find him. He calls as I pay for a cup of coffee and a muffin. Caught behind an accident at Stadium Way, Katz is stuck in traffic on Interstate 5.

I settle down at the corner of the cafeteria to wait for him. Steam from a nearby metal forge billows behind Gold Line tracks as they curve into Union Station. A few trains pass. Mist obscures most of the faint outline of the San Gabriel Mountains in the distance.

When Katz arrives I tease him about not riding transit to the meeting. He normally works from home and only comes to Union Station for Metro board meetings, he says. He often takes the Red Line from North Hollywood but will drive when he expects meetings to go late, as he did today. Just the day before he had been in Washington, D.C. for Obama's inauguration. There, he and Mayor Villaraigosa urged the incoming administration to change federal permitting rules to allow the state's environmental review documents in place of federal ones, thus cutting down on redundant reviews that might slow new projects down.

“We are looking to move the agency so that now we not only turn around projects faster and get them on the street faster and start building them faster, but we do it in green ways as well,” Katz says.

Lifestyle overhaul

Greening a community takes more than quickly building new projects, though. Tim Papandreou, Metro's former transportation planning manager, says any community that wants to be green has to completely overhaul its lifestyle.

“There is no city right now that is sustainable,” Papandreou said at a February conference hosted by the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. “Right now, we need to change the transportation gears, and we need to do it fast.”

Papandreou now works for the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Authority." Despite the broad overtones of the event he addressed, the third annual Expanding the Vision of Sustainable Mobility Summit, most of the event's discussion in fact centered upon new battery technologies and other ways to improve individual automobiles.

“Sometimes designing our way out of things is not the solution,” Papandreou told the audience.

Most people don't drive just because they think it's fun, Papandreou said. Instead, they are “literally forced to drive” because of current land use and transportation policies.

“Automobiles in current planning have more rights than we have,” Papandreou told the summit. “Cars have a right to housing, but humans don't.”

Papandreou, who hasn't owned a car this century, urged the audience to consider more systematic lifestyle changes in how we move through our lives, changes he says are already underway in the Los Angeles area.

A Farmers Market in a mixed-use building above Los Angeles’s Wilshire/Vermont Red Line Station, as seen in May, 2009. (Photo by Bill Lascher)

“Los Angeles is going through a massive transformation.” Papandreou tells me in an interview a week after the conference. “A lot of the stereotypes that people placed on L.A. in the 80s and 90s don't apply any more.”

The city's changing attitudes toward transportation could have an environmental payoff. Papandreou stresses the fundamental lifestyle changes that must happen; others, like Denny Zane, say policymakers must invest in lower emissions transportation systems, like light rail and subways. Zane, a former Santa Monica mayor and the political consultant credited with getting the ball rolling on Measure R, says that's why 35 percent of the $40 billion the new tax will provide will go towards rail.

“The real holy grail for transportation besides walking and bicycles is zero-emission, electric public transit,” Zane says. “We've been doing that for decades. We just haven't done enough of it.”

After convening an unlikely coalition of labor unions, environmentalists and businesses, Zane worked with state and local officials to craft Measure R into a palatable initiative. The campaign was tough, but Zane says the coalition was able to make its case fairly easily.

“I don't think it's rocket science,” Zane says. “Congestion really sucks and gas prices were really high.”

But just because Measure R passed, most people in transit circles don't believe the money will accomplish much if Metro pours it all into subways and light rail lines. Rail can be so energy intensive and expensive to build that it doesn't recover its costs.

Metro's bus fleet also cuts down on emissions. It has been called the nation's “largest clean-fuel bus fleet” because its vehicles run on compressed natural gas, a fuel touted for lower greenhouse gas emissions. However, some transportation experts say CNG vehicles spew more toxins than diesel engines equipped with emissions reduction technologies, claims environmental scientists and engineers continue to study. The debate has yet to be settled.

Some measurements of transit's environmental contributions can be deceptive as well. It's not enough to look at large ridership numbers and declare a rail line a success. Deeper analysis has to take place to determine whether the people riding those lines would otherwise have driven or if they would have taken a bus, biked or walked to their destinations.

What's certain is people are beginning to drive less, at least nationwide. The United States Department of Transportation released data Feb. 19 showing travel on all America's roadways dropped by 3.8 billion vehicle miles between December 2007 and December 2008. The drop partially coincides with a huge fuel price spike in the summer of 2008, but it continued even after oil prices plummeted in the fall (although it also coincided with a worsening economy in which more people are unemployed and not driving to and from work). In Los Angeles County, Papandreou attributes the changes to cities retooling their downtowns and neighborhoods and people deciding to live in transit-oriented communities where they can walk, ride bikes, or take buses and trains where they need and want to go.

“People are not purposefully not driving because they want to be green,” he says. “It just works for them.”

Passengers in Union Station. (Photo by Bill Lascher).

One afternoon I observe how it works at a coffee shop near the intersection of Vermont and Franklin Avenues in Los Feliz

Outside, steam and exhaust gather behind the tailpipe of a maroon Pontiac. The traffic shifts and the window of the coffee shop fills with a sheet of orange broken up by white letters reading “Metro Local.” The classical soundtrack dissipates momentarily beneath the whining brakes and chugging engines of the passing #180 to Pasadena. Vacant faces gaze through rain splattered windows, then turn forward as the light changes at the nearby signal.

The bus passes. More cars go by, their exhaust mirrored by gray wisps of vapor above a coffee cup. Moments later the windows fill with color again. This time the deep rumble carries with it a flash of fire-engine red. It's the #780. A Rapid.

It will eventually pass Vroman's Bookstore in Pasadena, where Pat Brown works. Brown doesn't ride the bus, but he does commute from here in Los Feliz via Metro Rail four to five times a week. Each day, he boards a Red Line train at Sunset Boulevard and Vermont Avenue and rides to Union Station. There he transfers to a Gold Line, which he rides to the Memorial Park stop. The trip can take between half an hour and an hour on the train. Were Brown to ride the #780, #180 or #181 bus, it would take about the same amount of time, assuming there are no significant traffic delays, according to Metro's Trip Planner Web site.

Brown hasn't always relied on rail travel. He and his wife used to share a beat-up car. Then they traded it in for a new vehicle. As gas prices skyrocketed last year they decided to make a point of not driving the new car too often.

Brown started riding the train regularly to work. The commute was easy.

“I get so much reading done,” says Brown, who, for some time ran Vroman's blog. “In general, I like the way the system moves. In general, I'm not on a train that breaks down, and when one does, they handle it well. It feels safe to me. That's not the case in every city. In general, I think they do a good job and for the things that they don't I think they have a good reason.”

Brown says as long as he takes the train during peak hours the experience is smooth, but he'd like it if trains ran later and more frequently at night and to more destinations. Still, in the meantime, Brown doesn't consider taking the bus as an option.

“I think I've taken public buses twice in L.A.,” he says.

While he thinks he could make sense of L.A.'s bus network if he focused on it, he says it's a confusing system. He'd ride it more often if it were obvious where buses were headed, and if there were more express buses available.

“The train in LA makes sense to me because you're bypassing the worst of L.A. The train doesn't have to go through traffic,” Brown said. He acknowledged critiques of rail which argue it doesn't serve low income riders, but he doesn't think buses are adequate transit solutions for Los Angeles. “Rail makes so much more sense in L.A. than buses do. The traffic doesn't seem to be going away, so buses add to that.”

Muddled Messages

Many who might take transit seem daunted by the idea of L.A.'s bus network, perhaps even scared by it. They don't know how to ride the bus, they don't know where it goes, when it goes or how often. To attract and retain these riders, Metro and other transit operators struggle to show how to conveniently take advantage of transportation alternatives.